The afoxés and blocos afros of Salvador are closely linked aesthetically, variations upon an African theme, the afoxés as a matter of ancestry and culture, the blocos afros – initially anyway and in the case of Ilê Aiyê certainly still – as an expression of black empowerment inspired in part by the civil rights movement in the United States.

Afoxé (ah-faw-SHEH) is basically candomblé with the religion taken out…the use of candomblé rhythms and “songs” and dance in social, non-religious settings like Carnival. The principal rhythm associated with afoxé is ijexá (ee-zheh-SHAH), a more subtle and complicated version of what you might hear pounded out on the Maxwell House coffee can for a late-hours Manhattan cocktail party conga line. On terreiros de candomblé ijexá is associated principally with Oxalá (the father) and Oxum (goddess of sweet waters), among other orixás.

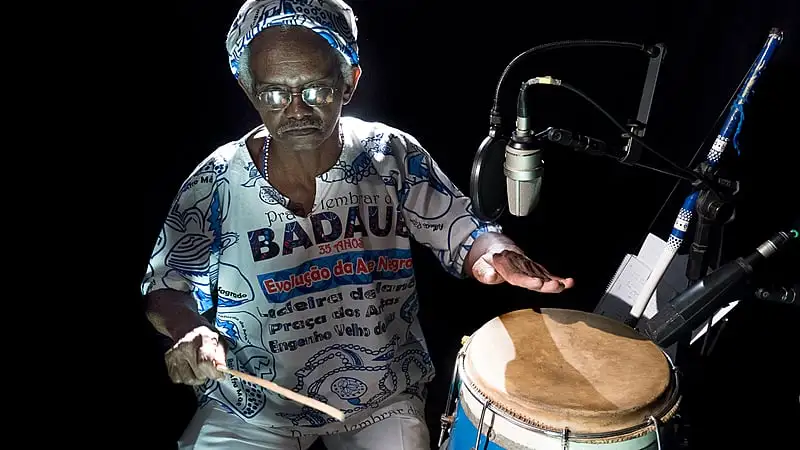

Embaixada Africana (African Embassy) was the first afoxé, parading in the Carnival of 1895. The next year afoxé Pândego da África (African Hijinks) went out, and in 1905 an afoxé climbed the Ladeira da Barroquinha to parade up the Ladeira de São Bento, thereby breaking a tacit understanding that the Carnival groups from the lower (and darker) economic classes had their areas (Baixa dos Sapateiros, Barroquinha, Pelourinho) and the upper classes had theirs (Avenida Sete de Setembro, Piedade). Salvador’s largest and most widely known afoxé – Filhos de Gandhy – was formed in 1949 by stevedores whose inspiration was the film Gunga Din and whose inspiration for the name was the great Indian leader and pacifist (who had been assassinated the year before). Other afoxés include or have included Filhos de Korin Efan, Badauê, and Filhas de Oxum. From 1904 until 1918 afoxés were forbidden to march during Carnival, ostensibly to combat “crime, ao deboche, e à desordem” (crime, debauchery, and disorder)”.

Blocos Afros are Carnival blocos (groups) which, put simply, celebrate cultural manifestations of African origin. The rhythms are usually based in what is called “samba afro” or “samba reggae” (which come in a number of variations) and the dress is African-inspired (in contrast to afoxé Filhos de Gandhy, whose robes draw their inspiration from the Indian subcontinent). Other blocos afros include Muzenza (from Liberdade), and Malê de Balê (of Itapoan), who drew the inspiration for their name from the Malê Revolt.

These groups – the afoxés and blocos afros – are by far the most beautiful and moving manifestations of Carnival in Salvador. The dances of candomblé, the intricate and powerful rhythms, the vestments…pure and powerful splendor! Most of the afoxés are relegated to the tiny Batatinha Carnival circuit, or the Terreiro de Jesus.

With respect to the name “Olodum”, the best known of Salvador’s blocos afros (both Michael Jackson and Paul Simon have recorded with them), principal founder Geraldo Miranda (popularly called Geraldão – Big Gerald), who went on to found Muzenza (a “muzenza” is an initiate into candomblé angola, the candomblé of the Bantus brought to Brazil; the word is from the Congo/Angola region), tells it like this (my translation):

“As for the name of the bloco, Olodum, I was the one who came up with it, thanks to a friend, a filha-de-santo (candomblé adept), who happened to mention that Olo and Dum were two deities, Olo representing the earth and Dum the heavens, without mentioning anything about their origins or if there was really any firm religious basis for this. I stuck the two names together and nobody disagreed and so it was, Olodum.”

Origins and religious basis aside, Olodumarê is the Yoruba name for the Supreme Deity, so Geraldão’s name worked.

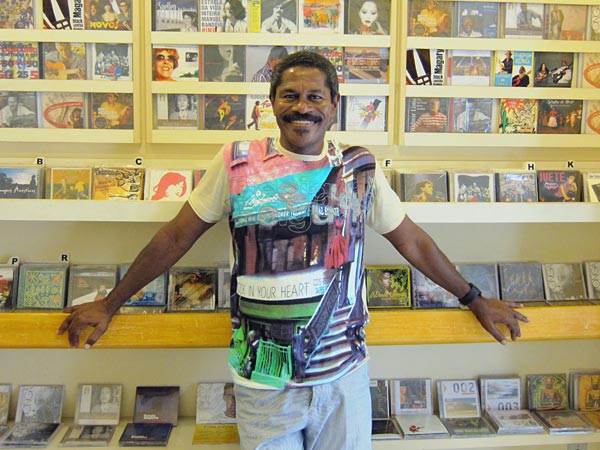

Olodum’s first president was Carlos Alberto Conceição do Nascimento, aka “Carlinhos”. Carlinhos and his wife Dona Vera have a great little place in Pelourinho, at Rua Maciel de Cima/João de Deus (the street has two names), 18: O Cravinho do Carlinhos, usually presided over by Dona Vera. It’s outside tables on a sloping street, two doors up from where I ran my record shop for 15 years at number 22. You’ll be waited on by either Maria (a powerful feminine presence) or Roque (a dapper older gentleman). I’m proud to have been crushingly embraced inside O Cravinho do Carlinhos after returning from Saubara, on the far side of the Bay of All Saints … purchasing my own cerveja at the little inside counter and saying to Compadre Washington (co-founder of Gera Samba/É o Tchan, the funnest musical group of all time!), a regular there (this is translated) “I’ve just returned from where your music was born… the Recôncavo!” And to complete a circle here, it was the fundamental rhythm of samba de roda — cabila/cabula — which formed the basis for Neguinho do Samba’s rhythmic interpretation for Ilê Aiyê when he was a member, before he went on to join Olodum and change their rhythms from Rio-style to his newly created Bahia-style. Samba de roda is in the DNA of most music here in Salvador, including that of the blocos afros.

Ilê Aiyê was the first “modern” bloco, founded in 1974 by Antonio Carlos dos Santos, popularly known, then and now, as “Vovô” (grandfather; a term which he’s grown into), and Apolônio de Jesus, popularly known as Popó, they having been inspired by the Black movements of the ’70s to create a Black carnival bloco. Vovô was dissuaded from his first choice for the bloco’s name, “Poder Negro” (Black Power), by his mother Mãe Hilda, mãe-de-santo (holy mother) for the house of candomblé around which the bloco was centered (Ilê Axé Jitolu), given the racism of the time. So they decided upon the Yoruba name for the world, “Ilê Aiyê” literally meaning “House of Life”. Ilê first went out for Carnaval 1975, singing what has become an anthem, Paulinho Camafeu’s Que Bloco é Esse? (What Block — carnival group — is This?).

And here I must personalize things: Some years ago, more than a decade, I was on my way from having closed the record shop to the birthday party of Giló do Pandeiro in Boteco do Dy, a no longer existing boteco on Rua Chile. Passing the Praça Municipal at the top of the Elevador Lacerda I saw and heard a musical presentation at the top of the steps leading into Salvador’s municipal headquarters, a wide area sometimes used as a stage … a large musical group playing a lovely and powerful song based in candomblé: Negrume da Noite (Darkness of the Night). And I thought to myself: “This is such a Salvador anthem…I really should know who wrote such a wonderfully iconic song!”

I go into Boteco do Dy, where the tables have been set in one large row like in a German beer hall, and sit down. And after a few minutes a gentleman comes in and sits directly to my right, and we introduce ourselves. He said he was a musician and composer and I ask him if he might have composed anything I might have heard in Salvador … and he says (em português) “My best known song is this… ‘O negrume da noite reluziu o dia, o perfil azeviche que a negritude criou…’ (‘The darkness of night illuminated the day, the ebony profile created by Blackness…’) This was Paulinho do Reco, who’d been a percussionist for Ilê Aiyê! And composer of the mighty song I’d just heard! Paulinho has lots of other compositions and is a sambista who plays and sings in rodas de samba around town.

The aesthetics of the blocos afros, in addition to musical, are visual. And they are stunning! The foundation of a seminal pattern-as-theme began with J. Cunha (José Antônio Cunha, born 1948), an artist, set and costume designer out of the Escola de Belas Artes da Universidade Federal da Bahia.

Another important Bahian aestheticist is Alberto Pitta. Pitta, as he is called here, has been artistic director for the Filhos de Gandhy, Ilê Aiyê, and for 15 years, Olodum. Pitta created the bloco afro Cortejo Afro, for which he created one of his trademark styles: white on white. Pitta also created the Instituto Oyá, dedicated to the intellectual and artistic development of children in his neighborhood of Pirajá and built around the terreiro de candomblé Ilê Axé Oyá, of which his mother is Iyalorixá, mãe-de-santo.