The concrete — or stone rather — reason for this neighborhood’s name was taken down and away on September 7th, 1835. But the metaphor remains, echoing through Pelourinho’s byways like the doleful remonstrances of aggrieved spirits.

“Pelourinho” means pillory. And Salvador’s pelourinho last stood at the top of the sloping Largo do Pelourinho, final point in a journey which began in the city’s first open market in the Praça da Feira (today known as Praça Municipal — the open square at the top of the Elevador Lacerda).

The pelourinho stood at the market’s center. Then sometime between 1602 and 1607 — period of the Governorship of Dom Diogo Botelho — the pelourinho was moved by governor’s decree to the Terreio de Jesus. But the Terreiro de Jesus was the site of the Jesuits’ church and school, and the screams and groans interfered with church services and teaching. So it was removed again and repositioned at the bottom of the Ladeira de São Bento (where Praça Castro Alves is now located).

Again it was removed, for the penultimate time, in 1807, and taken to the largo which would come to bear its name. It would stand there for another 28 years.

Spirits and Spirit of Pelourinho

Camafeu de Oxossi was a force-of-nature. Born in 1915 in Gravatá (across the street from Pelourinho), his father died when Camafeu was seven years old, and not liking the way he was treated by his new stepfather he lit out to fend for himself in the streets in and around Pelourinho.

Camafeu was baptized Ápio Patrocínio da Conceição, but according to Jorge Amado “Ápio Patrocínio da Conceição did not exist, it was just a nickname they gave him when he was born.” The christening was struck after a lucky run in a jogo de sorte, a gambling game, in Pelourinho. The guy he cleaned out called him “Camafeu” (a camafeu is a bas-relief cameo) after a lucky character in a film in town at the time. The Oxossi part came later, for this: Camafeu had a stall called Barraco de São Jorge in the old Mercado Modelo and São Jorge, or Saint George, is syncretised with the orixá of the hunt in candomblé, Oxossi. Voilà! A name fit for a legend!

Camafeu studied at the Escola de Aprendiz de Artífice close to Praça da Piedade, sold shoelaces, shined shoes, worked as a sailor and then later on the docks of Salvador, eventually coming to own a barraca (stand) at the Mercado Modelo (the first Mercado Modelo, which burned down in 1969, some say at the hand of the mayor).

Camafeu didn’t take the business seriously, partied with friends there, and wound up having to sell the place. The mercado’s administrator allowed him to put a couple of boards over an old fountain and at this makeshift stall Camafeu sold clothes and used shoes, eventually earning enough money to get back into the game, buying a couple of barracas, and then a couple more, all side-by-side, joining them together.

Here he sold materials for candomblé (he was an Obá de Xangô in house of candomblé Ilé Axé Opô Afonjá) and wandered the mercado aisles, berimbau in hand, singing the cantigas de capoeira (he was also a highly respected capoeira master).

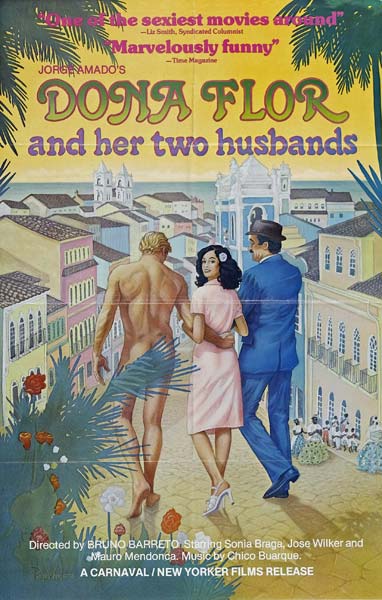

His barraca was, according to Jorge Amado, a meeting place, a nexus, a musical conservatory. Sr. Amado went on to say that culture in Salvador is born, nurtured, and affirmed in some pretty strange places. With his illustrious pen he immortalized Camafeu in several of his books, including O Sumiço da Santa (The War of the Saints), Pastores da Noite (Shepherds of the Night), and Dona Flor e Seus Dois Maridos (Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands).

Camafeu was a Filho de Gandhy and was the afoxé’s president from 1976 to 1982. He died in 1994 and at his funeral, while being interred in the cemetery of the Ordem Terceiro de São Francisco to the accompaniment of Catholic prayer, a song in Yoruba was lifted to the skies by babalorixá Luís da Muriçoca, and all present joined in.

Filhos de Gandhy

The Filhos de Gandhy headquarters (the spelling of “Gandhy/Gandhi” seems to inexplicably oscillate) is a culturally jamming place to be on Sunday evenings, from 4 p.m. (or so) until 10 p.m. (or so), between Brazilian Father’s Day (occurring sometime in August) and Carnival. Men dance as if in a house of candomblé, to live music — percussive ijexá — in the big downstairs hall, while friends and family eat abarás and drink soft drinks and beer on the mezzanine. The vibe is very, very good and the place gets very, very packed. Admittance is free. The address is Rua Maciel de Baixo (also named Rua Gregório de Matos), 53.

Filhos de Gandhy is an entity devoted to peace, the creation of which was inspired by an act of violence on the Indian subcontinent and the manifestations of which, although rooted deeply in Africa, were born in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil. And in common with one of the subcontinent’s great religions, Filhos de Gandhy was born beneath a tree — not a Banyan tree but a mango tree rather, growing on a steeply inclined street (Rua do Julião, now sometimes called Rua Campos Sales) running through one of Salvador’s poorest neighborhoods.

The men who were gathered there — stevedores, dockworkers — had no idea they were making history; they were simply honoring it while trying to have some fun. Carnival was about to begin and they were forming a bloco (carnival group) of their own. One of the men beneath the mango tree…Durval Marques da Silva — Vavá Madeira…suggested a name. It was suitable to all, and the theme followed naturally. A little more than a year earlier — on the 30th of January, 1948 — the great Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi had been assassinated. Vavá suggested that they honor this man who had fought so profoundly and achieved so much in a nation which — like their own — was racked by poverty and rife with social injustice, a man who wielded peace as a mighty instrument of change. The others liked the idea, and thus the Filhos de Gandhy — Sons of Gandhy — were born.

Peace would be their instrument as well, played out in the rhythms of ijexá on atabaques and agogôs. A Carnival bloco needs fantasias — costumes — and several of the men there under the tree had recently seen a film which made it to sleepy Salvador ten years after its 1939 release: Gunga Din, starring Cary Grant and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. It was an easy choice; the fantasias would emulate the clothing of Rudyard Kipling’s redoubtably intrepid waterboy…

Tho’ I’ve belted you an’ flayed you By the livin’ Gawd that made you You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!

But there was a problem. Shipping in the Port of Salvador had fallen off since the war and work was intermittent. On top of that the Federal Government — a dicatatorship — had announced post-war cost cuts and the stevedores’ income had taken a hit; money was tight. To the rescue came the working girls of the area — the ladies of Julião. Not only did they include (some, not all of) these men among their patrons, but they also included them as their friends. A number of the sheets utilized in the abadás (a name given to the flowing fantasias, based on the robes worn by the uprising slaves of Bahia’s 1835 Malê Rebellion) worn that first year were provided on loan by these women, and when the men paraded, the women followed, food and refreshments in hand. Like Dostoevsky’s Sonya Marmeladova, benevolence and generosity were not precluded by their profession.

Why did the women follow the men, and not march together with them? Nothing to do with social strictures. The concern was for the most part with the inevitable fellow-travellers who would join in from the sidelines and march along uninvited. The thought was that restricting the ranks of marchers to men — men who weren’t partaking of alcohol while parading — would help to ensure the reign of peace in that small part of the world over which the Filhos de Gandhy had some personal control. These were, of course, stevedores out for Carnival — not saints playing harps in Heaven — and drinking did happen on the sly. But the governing spirit of the rule was observed, maintained, and preserved, and the passing of the Filhos de Gandhy during Carnival in Bahia has since become an iconic emblem of dignity and brotherhood.

The Filhos de Gandhy started out as a bloco. They became an afoxé. What’s the difference? A Carnival bloco is any group which marches together during Carnival. An afoxé is a group which utilizes religious percussion and dancing in secular settings, the religion in this case being West African candomblé. Carnival blocos of the time included wind instruments and the Filhos de Gandhy played percussion instruments exclusively. Beyond this they sang to Ogum, Ologum-edé, Oxalá, Oxum, and Exu. The government body having to do with Carnival said they were an afoxé. The Filhos didn’t argue the matter; they voted on it. An afoxé in spirit, they became one on paper as well.

Years passed and the organization faltered. There were financial problems and the group moved from one headquarters to another. For all the axé (life force) they carried with them, no preordained upward trajectory seemed to leaven their path. Things got so bad at one point that it looked like the organization would have to fold. That it didn’t was in no small measure due to the efforts of extraordinary Camafeu de Oxossi.

Bright Melancholy and the Diplomat of Bahian Samba

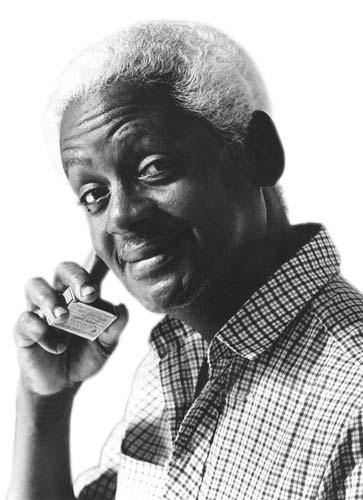

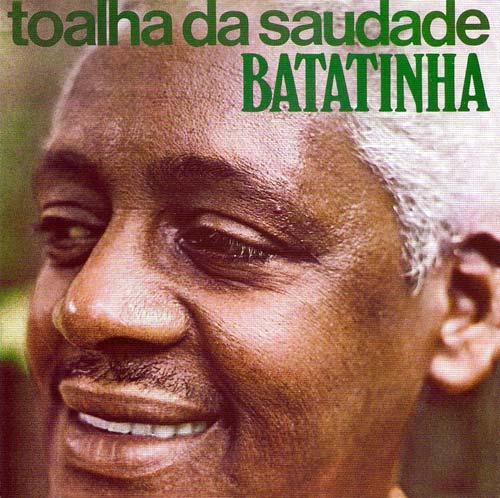

Batatinha (Oscar da Penha, born on the 5th of August, 1924 and in his youth a resident of Beco do Motta, 2) played the matchbox and composed many lovely sambas.

Among Batatinha’s many lovely songs is one with a particularly interesting provenance: Batatinha as a young man was out in the surging crowds that are part of Carnival in Bahia, when from the multitude emerged a lovely young woman, asking if she might borrow Batatinha’s small embroidered towel, a standard component of samba school carnival kits back then. Batatinha complied. The moça delicately dried her face, handing the towel back to Batatinha, thanking him before disappearing, never to be seen (by Batatinha) again…leaving behind in the towel her beguiling scent and sweet memories of what could have been had he perhaps taken the initiative…

The entire building above (including Batatina’s house) has been taken over by a fellow named Antônio, who is from the Brazilian state of Sergipe and who is thus and quite naturally called “Sergipe” (sehr-JEE-pee)…who runs a minimarket with the world’s greatest (cheapest) prices…which is where I tend to buy my beer in Pelourinho. Plus I (and a lot of other people) like the total lack of pretentiousness to the place (one can take one’s beers outside to the tables haphazardly scattered there).

Three artists who spent most of their time here in Pelourinho, at Cantina da Lua, are Batatinha, Riachão, and Ederaldo Gentil. Above find a clip of the three together singing a song of Ederaldo’s, Ederaldo singing and playing guitar to the accompaniment of the others. As always, Ederaldo’s lyrics are touching, movingly wrought. A translation into English follows…

Gold and Wood

Gold sinks beneath the sea Wood remains above Oysters are born of the sediment Creating fine pearls

I wouldn’t want to be the sea It would do to be the source Much less be a rose Simply the thorn I wouldn’t want to be the pathway Perhaps the shortcut Much less the rain Just the dew

I wouldn’t want to be the day Just the dawn Much less be the field Just one grain I wouldn’t want to be life Just the moment Much less a concert Just a song

I had the honor of meeting Ederaldo, one of Bahia’s great bambas (sambistas), a man so profoundly affected by the fall of samba from its place as the premier popular music of Bahia (to be replaced by what is now commonly called “axé music”) that he spun into a deep depression and for years didn’t leave his apartment, rarely seeing anybody but his immediate family (principally his sister Denise, who cared for him)…

Now, one might question the…stability or whatever one would like to call it…of somebody who would be so far derailed over the falling-from-popularity of one’s musical style, and the story is a complicated one (more complicated than I myself know), but Ederaldo Gentil had a good distance to fall. He was born in the area of Largo Dois de Julho and as a child was raised in the nearby central Salvador neighborhood of Tororó during a time (the ’60s) when Salvador had samba schools. Ederaldo belonged to the Filhos de (Sons of) Tororó. In 1967 his samba enredo Dois de Fevereiro won the school’s yearly contest, meaning that this was the principal song which the school would march to during Carnival. In the same year won Salvador’s contest for Best Carnival Song with a composition entitled Rio de Lágrimas (River of Tears). He went on to win the competition for Best Carnival Song for the next three years in a row. In 1969 Ederaldo had some sort of a disagreement with the Filhos de Tororó, resulting in the amazing fact (amazing to me, certainly) that of the ten samba schools marching in Bahia’s 1970 Carnival, nine of those schools went out singing an Ederaldo Gentil composition as their samba enredo! The only one that didn’t go out singing one of his songs was the one he’d had the disagreement with!

In 1972 he got back together with his companheiros in the Filhos, and the school went out that year with an Ederaldo Gentil composition celebrating the 50th birthday of Bahia’s most beloved mãe-de-santo (candomblé priestess) Mãe Menininha do Gantois, the samba In-Lê-In- Lá. This song also won that year’s competition for Best Carnival Song. In the years to come a number of Ederaldo’s songs were sung by Brazilian recording stars of national stature, including Alcione, Leny Andrade, Eliana Pittman, and others, and Ederaldo recorded several albums of his own. He was an established member of Bahia’s bamba* royalty (I call them the Bahian Ratpack), a group which played together and drank together (usually at Clarindo Silva’s Cantina da Lua, on the Terreiro de Jesus) and which included Batatinha, Riachão, Walmir Lima, and Edil Pacheco, all great sambistas.

In the late ’80s Carnival changed, and in Carnival ’91 Ederaldo and some of the other bambas tried going the axé music route, on top of a trio elétrico. It was a flop and that was the last straw. Ederaldo withdrew. 1999 a group of distinguished musicians including Gilberto Gil, Beth Carvalho, Elza Soares, João Nogueiro, and Carlinhos Brown recorded a record (CD) of Ederaldo’s compositions entitled Pérolas Finas in order to help him out financially. It has since become a collector’s item.

And so there I was, sitting in his apartment, addressing the man. He suffered from clinical depression. I asked him if he still played his guitar, and he answered no. He was sixty-five years old but surprisingly looked a good deal younger. I told him he wasn’t forgotten, much to the contrary. Among the cognoscenti of samba, he was a legend. I don’t think it registered. He’s dead now, but (among the cognosecenti), he is a legend.

* Bamba is an interesting word. In Portuguese it’s somebody whose legs sway (because for whatever reason — drunk, sick — they can’t support that person). In Kimbundo, spoken in Angola, it (mbamba) is somebody who is a master of something. In Brazil therefore and quite naturally, it is a master of samba.

Luiz Dórea…Nego Fua, the Rooster of Maciel (o Galo do Maciel), toughest guy in Bahia (retired), with scars from knife-fights and bullets to prove it.

Fua has lived at the corner of Rua Maciel de Cima (João de Deus) and Rua J. Castro Rabelo for some sixty years, with his Bar Galícia on the ground floor. Some years ago I personally saw him, aged and infirm, wade into a corner fight between two young guys, one armed with a knife, and break it up. Fua is a local legend and a sweet-tempered man, beloved by everybody in the community. His wife Morena sells churrasco (barbecue) on the corner on weekend nights.

There’s a great samba in Fua’s (run by his daughter Tati) on Friday, Saturday, and Tuesday nights, beginning earlier on Friday’s, 9:30 p.m. or so (sometimes if it looks like things are going to be to slow in Pelourinho the samba is cancelled).

Pelourinho Churches Rich, Poor, and Fallen

It’s almost as if Sr. Cravo has a thing for creating representations of fallen history. Another of his works is A Fonte da Rampa do Mercado Modelo (The Fountain of the Ramp of the Mercado Modelo), below in the Cidade Baixa (Lower City). This is on the location of and represents the old Mercado Modelo — city market — which burned down in 1969 (rumored to have been an act of the then mayor).

Salvador’s first customs house was built in the upper city by governor Tomé de Souza in 1550. Eventually somebody figured out that it would be easier to have one down by the water, within easy access of incoming ships, and a new customs house was built on the current site in 1861. It functioned there until 1914, when new harbor warehouses were constructed and customs tasks transferred to them. The abandoned and unused customs house was taken over by handicrafts sellers who moved over after the original Mercado Modelo (built in 1912) burned down (in 1969). There was a two-year wait while the customs house was refurbished, and it (or the new Mercado Modelo rather) has been operating since 1971.

A lay society of freed and not-freed slaves which had heretofore worshipped at a side-alter in the Igreja da Sé built their own church — construction beginning in 1704 — in the Largo do Pelourinho. These beautiful blue towers were only begun seventy-six years later, in 1780. Not surprisingly, the representations of the saints inside are of black men and women.

Nossa Senhora do Rosário (Our Lady of the Rosary) was the name given to the Virgin Mary by Saint Dominic (São Domingos de Gusmão, in Portuguese), founder of the Dominicans, who “received” a rosary from Mary in a church in southern France around the year 1200. The Dominicans founded the lay brotherhood of the Rosary in Cologne, Germany, in 1408…the brotherhood arriving in Brazil in 1685 and eventually becoming a society of black men. Before they built their own church the brothers met in one of the side altars of the Igreja da Sé (which was located in today’s Praça da Sé and destroyed in 1933 in order to provide a convenient turn-around for Salvador’s street cars) before a statue of Nossa Senhora do Rosário. The statue was eventually transferred to their new church and remains there to this day.

I’d venture to say that this is the only building in Old Salvador that wasn’t built by slave labor, given that the enslaved involved in building it were building it for themselves… A special mass is conducted on Tuesday evenings at 6 p.m., with Yoruba drumming.

Not to be confused with Olodum’s drumming per this Spike Lee clip filmed in the Largo do Pelourinho (although the drumming to Michael’s music is another matter, the general style that Olodum plays has its origins in the drumming of Ilê Aiyê, and that was a stylization of samba de roda, a creation of Bantus in Bahia; the Yoruba came (were brought) later:

Thijs Weststeijn has a beautifully conceived and written monograph on the cloister azulejos here…

To the left of the Escola de Medicina is the church which gave the Terreiro de Jesus its name. This is the Catedral Basílica, and the name in question is derived from the fact that the cathedral was founded by the Jesuits.

More specifically, the cathedral was founded by Jesuit Father Manoel da Nóbrega, who, among other activities, enslaved Indigenous for use in forced labor…time repaying his holiness by making the last part of his last name (brega) synonymous in Brazil with lowest-class bars, the music played in them, and prostitution (this because a street which once bore his name was lined with such).

Father Nóbrega wasn’t the only member of the Society of Jesus to engage in extremely un-Jesus like activity. The Society accumulated sugar plantations (worked of course by enslaved), cattle ranches…prospering mightily until their unholy butts were kicked out of Brazil in 1759.

Under the cathedral’s main altar is buried the third governor-general of Brazil, Mem de Sá, scourge of the Caeté Indians (declaring war upon them for having eaten Brazil’s first bishop; but quid pro quo His Excellency was an enslaver of Indians).

Mem de Sá was father to Estácio de Sá, founder of the city of Rio de Janeiro. Estácio’s name was given to a neighborhood (Estácio de Sá, quite naturally) which would become home to a teaching school (Escola Normal). It would also become home to a bunch of kids who in the late 1920s wanted samba better suited for marching in Rio’s Carnival parades than the dance samba imported from Bahia. For this they would sideline what Jelly Roll Morton, speaking of the New Orleans jazz of his time, called “the Spanish tinge”; the habanera, the one two, and one two, and one two that powers Bahian samba…and by doing so give birth to samba carioca. These kids would also say that while the school there in Estácio taught people to teach, they taught people to samba. They were a samba school! Giving form to one of the two things that Brazil is most internationally famous for (along with football)… That faint rumble you hear from the cathedral is Mem de Sá spinning in his grave.

And finally, there is no marker to reverse-commemorate the spot upon which stood the column to which slaves were bound, beaten, humiliated and tortured…there’s only the name, and it’s incumbent upon us to make of that what we will.