In Rio de Janeiro, in the house of a Bahia-born ialorixá (priestess) who had arrived in Rio as a young woman (part of the exodus of emigrating Bahians leaving for the capital in search of work around the time of Brazil’s abolishment of slavery), the music (in the front part of the house anyway, more on out back in a bit) was…

…So everybody has heard of killer bees, right? The Africanized version of European honeybees? The music in the salon of Tia Ciata’s house was an Africanized version of the music from which it had descended (polkas, waltzes, mazurcas) after first being played some 40 years earlier for the monied classes by musicians from Brazil’s darker classes. The Brazilians took the European rhythms’ metronomicity and made it — subtly but unmistakably — breathe, giving it ginga (sway), and in doing so freed the music to swoop, hover, dive and soar.

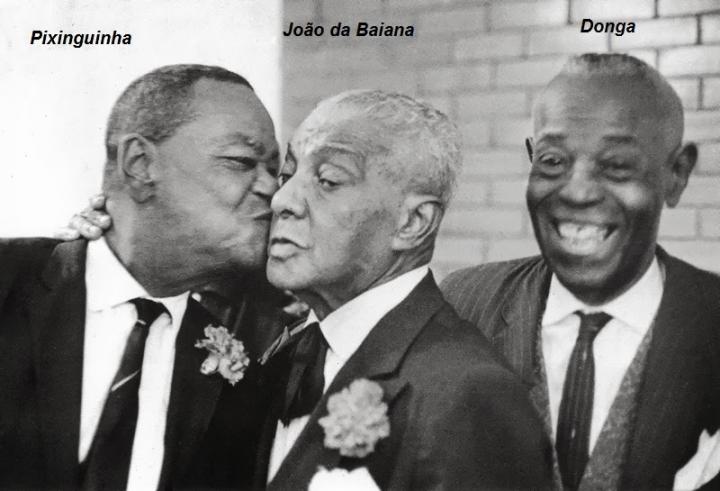

Strange to say, this music, called choro — or “cry” — is almost unknown outside of Brazil, as is its killer (in oh-so-gentlemanly a way) king, Pixinguinha (his given name was Alfredo da Rocha Vianna; his nickname was a version of what he was called by his African grandmother).

These guys weren’t cool for nothing. Like the American jazz players whose style followed (and would later come to influence) their own, they were masters of their instruments. This was and continues to be a dominating element in choro, as beautifully illustrated in an offhand clip of Raphael Rabello at a friend’s place playing Tico Tico na Fubá (composed by Zequinha de Abreu in 1917)…

In 1989 Raphael severely fractured his right arm in an automobile accident and was forced to undergo a number of surgeries. During this period he received blood contaminated with AIDS, which would take his life in 1995. He left behind a number of consummate recordings. Here’s the trailer to Mika Kaurismäki’s 2005 choro documentary, Brasileirinho, featuring a number of currently active players…

So Brazil had elegant men in tuxes playing music that required the finesse of classical instrumentalists and the improvisational prowess of jazz musicians, and had/has hotfingered young (and not so young) players working in this erudite idiom in our time…but what about the samba, you may be thinking? The uplifting energy, the sheer noisy joy of it all?

Well, below you’ll hear a samba in a style incipiant to partido alto, a style popular right up to this day (a notable characteristic of Brazil is that Brazilians tend in most instances to not discard their music; it accretes rather, and styles which would analogously be played as period music in the United States, ragtime for example, are played here as if they’ve simply never gone away, which they haven’t!).

The man seated to the right in the photo of the men in tuxes up the page (Os Oito Batutas) is Ernesto Joaquim Maria dos Santos, better known to his friends and to history as Donga. Donga participated in both the composition and performance of the first ever carnival samba recorded (and referred to as such) in Brazil, Pelo Telephone (By Telephone).

Where was Pelo Telephone (nowadays spelled, in keeping with official changes in Portuguese orthography, Pelo Telefone) written? Right! At Tia Ciata’s house! It was sung by Bahiano (Manuel Pedro dos Santos), so called because he was from Santo Amaro, Bahia, and it was the big hit of Carnaval 1917.

And what was by telephone? Rio’s chief of police had (apparently) let it be known to the bicheiros running the jogo de bicho (animal games), a common gambling game (still existent and highly involved in financing Rio’s Carnival schools), that they’d be advised by telephone when there was about to be a raid, and this had become common knowledge. The song’s original lyrics dealt with this humorously, and were changed in the recorded version.

Why would such a samba come to be written in Tia Ciata’s house? Tia Ciata, whose real name was Hilária Batista de Almeida (Brazilians love nicknames), was born in Santo Amaro, Bahia in 1854. She emigrated to Rio in 1876 at 22 years of age, settling close to Praça Onze, a public square in an area called Cidade Nova (New City), this area aptly nicknamed by one its illustrious residents, sambista and painter Heitor dos Prazeres, as Pequena África (Little Africa).

Most of the residents of Pequena África were, if not personally, then moving back a generation or two, of Bahian origin (Donga’s mother and father, for example, were born in Bahia), and the Bahian movement to Rio was accompanied by their religion (candomblé) and its ceremonies.

Now, by this time the dominant strand in this religion had become that of the last ethnic group (broadly speaking) to be taken to Brazil, that of the Yorubas. Yaô (sung by João da Baiana, whose mother — as indicated by his nickname — was from Bahia) is named for the title given to an initiate into candomblé Ketu, which is the candomblé of the Yorubas.

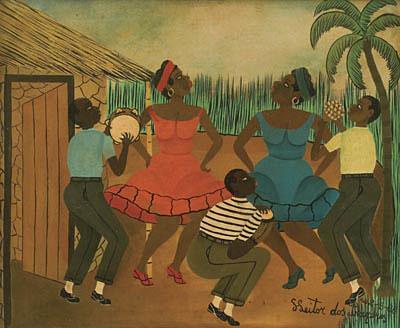

The song is about a festa of female yaôs, including mentions in the lyrics of Ketu orixás (deities) Ogum, Oxalá, Yemanjá, Oxossi, Nanã Buruku, and Xangô. But the drumming, singing and dancing which came after the candomblé ceremonies in both Bahia and Rio — and by extension in the quintal (backyard, so to speak) of Tia Ciata’s house — was not that of the Yorubas, it was that of the the first ethnic group to be forcibly brought to Brazil, principally to Bahia, the Bantus. And in their candomblé ceremonies, a candomblé referred to as candomblé angola (in obvious reference to the territory of the practitioners’ origins), the rhythms were built around what in secular settings would come to be called…that’s right!…samba!

From this point on samba in Rio de Janeiro was on its own path. It would flower and fluoresce in an urban culture, climb the morros (hills) of Rio along with the poor who had nowhere else to build their barracos (shacks), it would become the music of radio, music written by men of the morros and sung by radio stars who earned vastly more, and it would become the music of a carnival which would eventually become established at Praça Onze and which nowadays parades inside a vast Sambódromo located where Praça Onze once stood, as did the house of Tia Ciata.

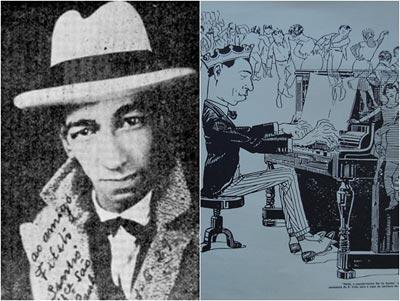

Before leaving Tia Ciata’s house and its enormously influential place in the history of Brazilian music behind, another assiduous participant in the rodas de samba there was José Barbosa da Silva, better known then and now as Sinhô, o Rei do Samba.

Before the age of radio stars had really kicked in (due to a number of factors including a change from broadcasting classical music to popular, the introduction of new microphones allowing more nuanced singing, and the wider proliferation of radio receivers), Sinhô and his music were everywhere. This was most definitely samba (Sinhô worked in other, related musical idioms as well), played within samba’s metrical structure(s), but to uninitiated listeners it might not sound all that much like samba, being sometimes referred to as samba amaxixado.

“Amaxixado” comes from the word maxixe, which referred first to a dance and then to the music played to accompany that dance. Actually, a maxixe is a vegetable common enough in Brazilian kitchens, but how a dance came to be named for a vegetable is a mystery. One version is that the dance’s inventor was somebody nicknamed Maxixe; another is that the dance’s lowly stature (it was a couples’ dance wherein the man stepped well in between the woman’s legs) was being metaphorically paired to the fact that maxixes grow along vines on the ground (I doubt this version, at least the first sounds plausible). But whatever the case the music combined elements of lundus and polkas, lundu being a shortening of calundu, calundu being a religious celebration which bequeathed a dance (lundu) in secular settings, which begat a style of music.

Anyway, maxixe was played without percussion instruments, so pretty much any samba played likewise either received the appelation amaxixado, or was simply referred to as maxixe.

Bide invented an instrument commonly used in samba now, the surdo (a big bass drum; “surdo” means “deaf”), making the first one from a large can which began life as a container for butter, and the sambas in Marçal’s house included Francisco Alves and Orlando Silva, two golden-throated singers of Brazil’s golden age of radio.

Cartola, a man (nick)named for a hat, is considered by many to be the apotheosis of samba. In 1949 the new president of the Mangueira samba school chose a professor of music to choose Mangueira’s samba enredo (Carnival samba) for that year.

Nelson Sargento comments: “O professor escolheu o meu samba. Mas ele explicou: pela beleza, pela perfeição, por tudo, ele daria 10 para o do Cartola, e 6 para o meu. Agora, para o desfile, o meu era mais fácil, era melhor. O do Cartola, em termos de hoje (1949), não era comercial. … A música dele era muito elaborada, a linha melódica muito difícil.” “The professor chose my samba. But he explained that for beauty, for perfection, for everything, he’d give a 10 to Cartola’s composition and a 6 to mine. But for the parade, mine was easier, it was better. Cartola’s, in today’s terms (1949), wasn’t commercial. … His music was elaborate, the melody line difficult.”

But let’s back up for a moment, to the other golden-age-of-radio singer who frequented Marçal’s house, Francisco Alves. Sr. Alves was stopped in the street one day by two penniless young men and asked for money. He responded that he would honor their request if they would each compose a samba for him, right there and then, on the spot.

So right there and then he received from one of the young men Qual Foi o Mal que Eu Te Fiz? (How Did I Wrong You?), which he recorded in 1932. From the other he received Estamos Esperando (We’re Waiting), which he recorded, together with Mario Reis, also in 1932.

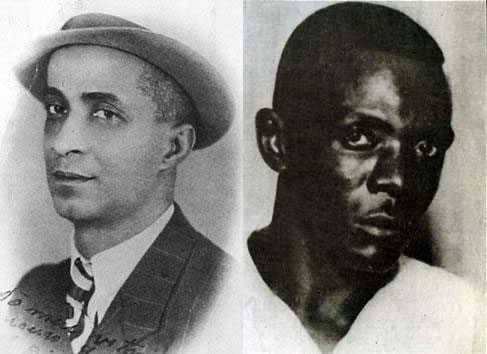

As one might guess, these weren’t just any two penniless bums, they happened to be two empty-pocketed young geniuses, Cartola and his buddy Noel Rosa. Noel Rosa was a fragile young man made more fragile by his inability to eat solid food, result of a botched wrenching by forceps during a difficult birth, breaking his jaw before he’d even parted with his mother’s womb (coincidentally and somewhat amazingly, the physician attending Noel’s birth would — sixteen years later — attend the birth of another future legend, Antonio Carlos Jobim; the doctor who wielded the infamous forceps however was a colleague who’d been called in to assist).

Noel was operated on twice as a child and his mother was told that his condition would improve with time, but it only worsened, imprinting upon the young man (dead at 27) an unlikely and unmistakable profile beloved by the masses of his time and by generations of samba afficionados thereafter.

Noel’s Com Que Roupa? (“With What Clothes?”) was THE smash hit of Carnival 1931, its inspiration coming when Noel’s mother, not wanting her son to risk his health by going out to a samba with his friends, hid his clothes.

His galera (group of friends) arrived, calling up for him to come out, only to see Noel lean out the window and reply “With what clothes?” (history doesn’t record whether he ever eventually got to the samba or not).

With what clothes? become the catch-phrase of the hour in the mouths of a people deeply devoted to sociability while at the same time deeply mired in poverty.

With the ’30s Brazil entered the radio age in earnest, broadcasting moving from erudite music to popular, and at this point there was a fork in the road: The songs were written drawing upon a vast heritage of forms and rhythms played and sung and danced to wherever people gathered for pretty much anything other than church: the botecos (bars), the quadras (yards) of the samba schools, the quintais (backyards).

But they were sung by golden-throats in an evolving style closely matching what was popular in the United States at the time, and for this the aural record is written almost exclusively in these beautiful “radio” voices.