This is a download of 51 Brazilian LPs/CDs as 320 kbps mp3s, in a zip file (4.35 GB). 662 songs, around 34 hours playing time.

The download includes Brazilian music that is unknown outside of Brazil. There is some bossa nova, but more samba, including deep roots samba from Bahia, where it all began on the sugarcane plantations around Bahia’s great bay (lots of information on various pages of this site about this).

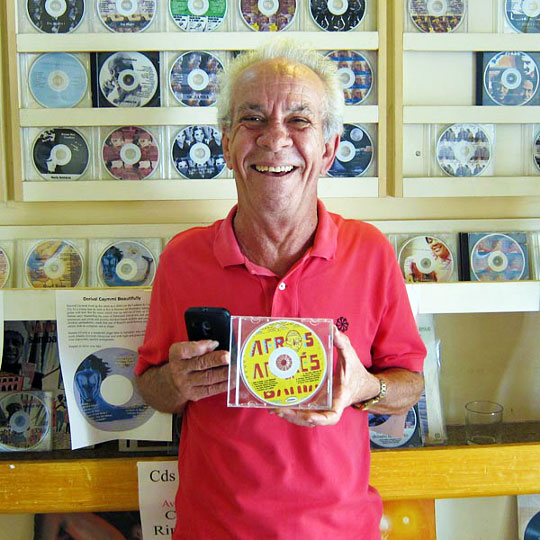

This download is the Holy Grail of Brazilian music. It was compiled in our record shop here in Brazil, Cana Brava Records, where we have access to music that nobody else has.

Contact me via whatsapp at +55 71 9976-2049 or sparrowroberts@gmail.com, and I’ll send you a download link. I’ll happily answer any questions about this, about sending LPs, etc!

After you’ve received and reviewed the music, you pay what you want via PayPal. In the shop we sell this as a pen drive, for 150 reais, equal to around 38 dollars or 34 euros. But it’s up to you!

Information on the music below. I’ll be adding to it as time permits!

Musical Genre: Samba de Roda / Samba Chula

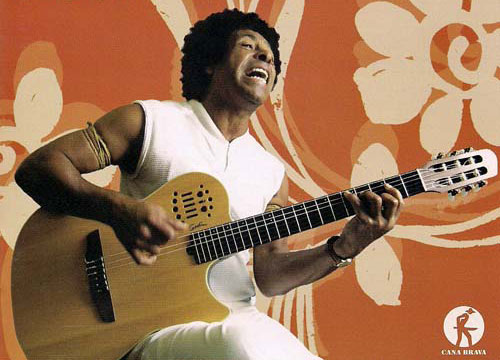

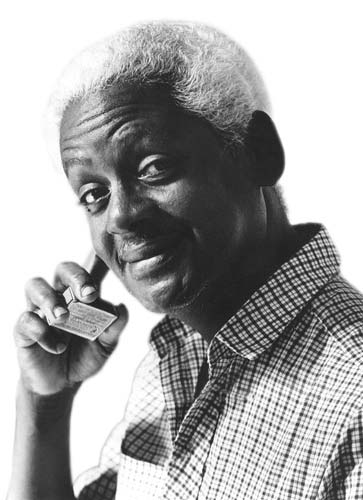

Dengo by Raimundo Sodré of Ipirá, Bahia (currently residing in Salvador)

This is chula and samba-de-roda and forró and ijexá…music of Bahia’s Recôncavo and sertão (backlands)…

It moooooooooves like an electron quantum-dancing around a hydrogen nucleus in the solar corona!!!!!!

There are 13 tracks on this record.

Raymundo Sodré (the last name is pronounced “saw-DREY”) is one of the most fundamentally important musicians in Bahia…at the forefront of a handful of people who play a very African style of samba which predates and is a precursor to Rio-style samba, a style which could be said to be analogous to the blues in the United States (although far more rhythmic).

Bahian samba is samba-de-roda (roda is “circle”) and this samba dates back to when enslaved Bantus on Bahia’s sugarcane plantations would gather into circles, clapping and singing, one slave inside the circle showing off is or her hottest moves. This was the slaves’ manner of turning misery – for a short time anyway – into the sublimely elemental joy of simply being alive.

Raymundo is also heir to Luiz Gonzaga and Jackson do Pandeiro, last in a great triumvirate of masters of the moving music of the sertão), the hardscrabble backlands of Brazil’s Nordeste, or Northeast).

DENGO (“dengo” is a desire for affection) is something of a culmination for Raymundo, who returned to Bahia 22 years ago after years of exile imposed when he was threatened with death after a show during which Raimundo spoke out openly against the dictatorship (in force until 1984).

Before his exile, Raymundo was one of Brazil’s brightest stars (his protest song/hit “A Massa” — Dengo’s second track – was an absolute phenomenon in Brazil in 1980) and now his star is rising again to take its right place over the Recôncavo (plantation region around the Bay of All Saints) and sertão.

Like the blues, samba is a genre where the musicians – steeped in tradition – just get better with time, and Raymundo Sodré is at the top of his form. He’s one of a handful of the greatest representatives of his/their wonderful (although dying out) style of music, the very style which would eventually develop into the national music of Brazil. Viva!

Chulas by João do Boi (and Family and Friends) of São Braz, Bahia

There are 9 tracks (some of them are looooong) on this record.

Samba-chula (or samba-de-roda, there is a slight difference) is a seminal but dying art played nowadays by a mere handful of people. The music fulfilled a role analogous to that of the delta blues in the United States in that it was/is the root foundation for most everything which came after it in Brazil’s musical world, from the golden age of radio to bossa nova to tropicália to Brazilian hip hop. And ironically and in total contradiction to the situation of the blues, this cornerstone of culture now finds itself precariously close to disappearing forever (although those last legs certainly do have some life left in them!).

“Chula” is a Portuguese-language word denoting something worthless, of no value. It was applied by the masters to the music of the Bantus on the sugarcane plantations of the Bahian Recôncavo, coming to be innocently used by the slaves themselves and eventually metamorphosing into a term of pride. The rhythmic basis for samba-chula is that of the candomblé rhythm called cabila, or cabula, utilized in candomblé angola (candomblé is the West African religion transplanted to Brazil aboard the negreiros; candomblé angola was the first of the three candomblé nations to arrive on Brazilian soil.) Laced into the polyrhythms of the atabaques, pandeiros, and rebôlo are the patterns of the cavaquinho (a small, high-pitched string instrument), the viola (a double-strung guitar-like instrument, though smaller), and the violão (guitar); (specific instrumentation varies from group to group). The dancing style — precursor to the more ostentatious style of Rio de Janeiro — echoes that of candomblé angola ceremonies.

Towards the end of the 19th century there was a huge outpouring of freed Bahian slaves moving to Rio, looking for work. These people carried their music with them to the territory around another great bay (Guanabara), where their descendents, forced up into the morros (hills) would come to see this heritage rise from its lowly-esteemed position to proudly assume the mantle of the National Music of Brazil. But not all freed slaves would make the journey south, and in Bahia the primordial samba, samba-chula, would live on, sublimating away over the course of a century-and-some-decades like vapor from dry ice until now almost nothing is left behind.

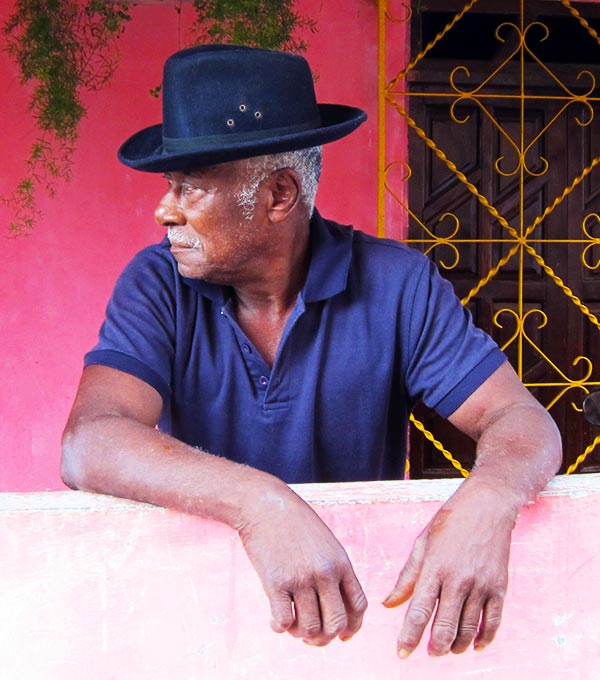

Of the few people left in the backwaters of Bahia who continue to sing and play this essential music (having learned it from their parents, who learned it from their parents, who learned it from…), it can be safely stated that none express it with more vitality and charisma than the Saturno Brothers, João and Antônio, popularly known as João do Boi (John of the Ox, for the cows he keeps) and Alumínio (Aluminum, for the way he shone, literally, as an energetic, sweat-drenched kid on the football fields of his youth).

The brothers play together with friends and family from the small community of São Braz, located some 5 kilometers outside of Santo Amaro, itself located at the north end of the Baía de Todos os Santos (Bay of All Saints), the huge bay “discovered” by Amerigo Vespucci on All Saints Day in 1501 (Santo Amaro is hometown to Caetano Veloso and his sister Maria Bethânia).

Samba de Roda: Patrimônio da Humanidade by people of the Recôncavo

There are 22 tracks on this record.

This is a collection of twenty-two recordings of thirteen traditional groups in the Bahian Recôncavo (birthplace of Brazilian samba), these recordings taking place in the communities of the artists themselves as a part of the dossier for samba de roda’s candidacy for official recognition by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (which was granted).

Released January 6, 2005

Research Coordinator: Carlos Sandroni

Researchers: Ari Lima / Francisca Marques / Josias Pires / Katharina Doring / Suzana Martins

* The photo is of Dona Dalva de Cachoeira — who has gone from singing (cigar) factory girl to grand matriarch of Bahian samba — seated in front of house (I took the photo).

Terreiros de Samba Chula – Roque Ferreira

There are six tracks on this record.

Roque Ferreira was born in Nazaré das Farinhas, just south of the southern end of the Baía de Todos os Santos, and raised in Salvador. He’s had songs recorded by Clara Nunes, Maria Bethânia, Zeca Pagodinho, Alcione and others. Roque’s passion is the music of the Recôncavo, and this recording is of — for the most part — public dominion folk songs from the region.

Musical Genre: Samba da Bahia*

Dorival Caymmi – Caymmi

There are 13 tracks on this record.

Immortal Dorival Caymmi is strangely unknown outside of Brazil. Born in 1914 in Salvador’s neighborhood of Mouraria, he left for Rio in 1938 to look for work as an illustrator, where he kind of fell into a music career. Caymmi is one of those musicians whose compositions are infused with and evoke the region wherein they were conceived.

This record was recorded in 1972 and unlike many of Caymmi’s recordings doesn’t have the heavy hand of the record company behind the sound. It’s very elemental and candomblé-influenced (Canto de Nanã above is straight candomblé).

Jussara Silveira & Luiz Brasil – Canções de Caymmi

Dorival Caymmi lived up the street from the record shop as a child (on the Ladeira do Carmo, 35). As a young man he went to Rio to become an illustrator, taking his guitar with him. But the music which rose up and out of him, as if he were Bahian satyr channelling the souls of fishermen lost at sea, and candomblé priestesses and orixás and poverty-stricken beach urchins and sensuality-stricken sambadeiros…made him one of Brazil’s most famous musical artists, both as composer and as singer.

Jussara Silveira is a wonderful singer here in Salvador, who within this work inhabits Dorival’s Dionysian soul with light and grace and swing, over impeccably tasteful arrangments.

Prepare to move your hips.

Ederaldo Gentil (Salvador’s True King of Carnival)

Nowadays Carnival in Salvador is dominated by blocos, but in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s Salvador had Carnival schools based in the original Carnival school tradition of neighborhoods.

Ederaldo Gentil was a kid from the central Salvador neighborhood of Tororó who worked as a watch repairer. He joined the Filhos de Tororó (Sons of Tororó) as a ritmista (rhythmist, or percussionist) but soon stood out for his talent as a composer. His first samba enredo (Carnival samba) was Dois de Fevereiro (named for the date of Salvador’s huge festival for the deity Yemanjá).

In 1969 Ederaldo had some kind of a misunderstanding with the management of Filhos do Tororó, and in 1970 something unique in Salvador’s (and undoubtedly the world’s) history happened: Of Salvador’s ten Carnival schools, nine went out singing compositions by Ederaldo Gentil. The only one which didn’t was (of course) the Filhos do Tororó.

Through most of the ’70s Ederaldo won Salvador’s Municipal contest for best Carnival song every year. But in the mid-’80s there was a sea-change in Salvador’s Carnival music: Axé music (frothy, LCD pop) took over. Samba was out! In an attempt to revive the Carnival samba scene a trio elétrico was launched with Salvador’s Velha Guarda (Old Guard, although they weren’t so very old), and it was a total flop. Nobody cared anymore. Ederaldo went into deep depression, from which he never recovered. He passed away a couple of years ago, not having touched his guitar in years. But he left a wonderful legacy of brilliant sambas laced with candomblé and chula…truly essential Bahia!

Batatinha – Diplomacia (Pelourinho’s Wondrously Wistful Genius of Samba)

Oscar da Penha – nicknamed “Batatinha” – lived as a small child on what is now Rua 3 de Maio (formerly Rua dos Campelas) in Pelourinho (off of Praça da Sé), and then on the Beco do Motta, in part of what is now the corner bar/grocery (around the corner from Cana Brava Records).

“Batatinha” derives from “batata”, a Bahian version of “bamba”, Brazilian slang for a sambista of great ability (bamba itself being a conflation of the African term bamba, a person of great renown, and the Portuguese term bamba, somebody with weak or crazy legs, i.e. somebody dancing samba). When Antônio Maria first used the term batata for Oscar on a radio show, it was Oscar himself who modestly applied the diminuitive inha. And the name stuck.

Batatinha was first recorded by Jamelão, the great interpreter of the Mangueira samba school, and then repeatedly by Maria Bethânia. Batatinha himself was recorded several times, the last being in 1997 (by J. Velloso and Paquito, who worked well and hard to capture and rescusitate Batatinha’s obra, much of which was committed only to his memory). This disc was the lovely Diplomacia, which Batatinha himself never lived to hear.

Salvador’s Carnival circuit running through the old Cento Histórico was named in honor of this man who so marvelously captured and artistically transmuted life in Bahia.

Rosa Passos (de/from Salvador), *música de Ary Barroso (Minas Gerais)

Rosa sings her sophisticated versions of Ary Barrosos’s songs (one apt enough comparison might be Ary Barroso as popular songwriter in Brazil is George Gershwin as popular songwriter in the United States).

Musical Genre: Samba dos Blocos Afros & Afoxés

Afros e Afoxés da Bahia (Salvador’s Carnaval Negro)

There are 10 tracks on this record.

Released in 1988, this is the best recording of Bahia’s Black Carnival music ever made. Each song is either a samba-afro/samba-reggae, played by a bloco afro, or an ijexá, played by an afoxé, each song sung by a different singer.

Samba afro/samba-reggae is/are built on variations of traditional samba, some of them with an altered swing, its primary creator being Neguinho do Samba when he was with with bloco Ilê Aiyê (the house across the street and one-house-over from Cana Brava Records belonged to Neguinho, who has since passed away; the house is now in the hands of his daughters and was bought for him by Paul Simon).

An afoxé is a group which plays a candomblé rhythm outside of the religious setting of a house of candomblé, this rhythm being ijexá (named for a group of tribes in what is now Nigeria).

On Afros e Afoxés da Bahia, all songs were written by Edil Pacheco (who was also the music director), with lyrics by Paulo César Pinheiro, one of Brazil’s most famous lyricists (and husband of the divine Clara Nunes). If you’re lucky you might catch Edil drinking beer at O Cravinho on the Terreiro de Jesus.

Musical Genre: Candomblé

Cantigas de Oxalá

Cantigas (songs) for candomblé deity Oxalá, sung in various houses of candomblé in the Salvador metropolitan region. These houses are divided between Ketu, Jêje and Angola, reflecting the various regions (now Nigeria, Benin and Angola/Congo) from which Africans were transported to Bahia over time.

Luís da Muriçoca – Candomblé de Ketu

Luís da Muríçoca (literally, “Luís of the Mosquito”; his house of candomblé was in Salvador’s Vale das Muriçocas, Mosquito Valley) was a pai-de-santo — candomblé priest in the Ketu (a region of what is now Nigeria) tradition. This is an entire xirê, candomblé ceremony.

Musical Genre: Music Based in Candomblé

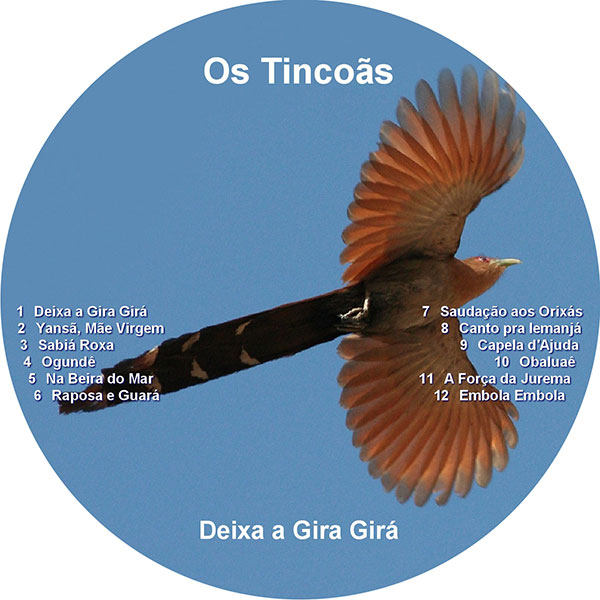

Os Tincoãs 1973, of Cachoeira, Bahia

A tincoã is a bird native to wide swathes of South America, called by many different names, including in Brazil “alma-perdido” (lost soul) due to its strangely moanlike song.

Os (The) Tincoãs was a trio from Cachoeira on the Paraguaçu River, singing songs of their own composition…based in candomblé…in a vocal style based in black American spirituals.

The principal songwriter was Mateus Aleluia who continues to compose and sing, enveloping listeners in beautiful axé emanating from the Roça de Ventura (the house of candomblé in which Mateus was raised) on the outskirts of Cachoeira.

The image on the CD above is not taken from the LP. The image on the LP is of the trio on a beach in something like faux capoeira pants. It was taken in Rio and is kind of a fake idea hatched by the record company’s art department. I decided to just go with a tincoã.

Agô – Cantos Sagrados

Grupo Ofá – Odum Orím: Festa de Música (pessoal de/people of Gantois terreiro de candomblé)

Musical Genre: Samba Carioca

A Velha Guarda da Portela – Tudo Azul

Portela is a samba school in the northern suburbs of Rio de Janeiro, home to a magnificent tradition of lovely music sung by lovely people over polyrhythms stretching back through Bahia to the Congo.

Tudo Azul (which is a Brazilian expression meaning “Everything’s great!”) brings together Portela’s Velha Guarda – the old and great guys and women (although when the Velha Guarda was first formed the “old guys” were barely 40, if that; it was twenty-something Paulinho da Viola who was behind the group’s formation, Paulinho being in his hale-and-hearty seventies now)…in a production where the sound of “production” is absent, leaving what should be heard: the music and the people making it.

The record was produced by Marisa Monte, whose father was one of Portela’s directors. It is without a doubt one of the greatest samba recordings of all time.

Aniceto do Império – Partido Alto Nota 10

Aniceto de Menezes e Silva Jr. — Aniceto do Império — was a founder of the Rio carnival school Império do Serrano. From the time he was a kid he was noted for his facility with words, and as an adult he divided his time between his work as a stevedor on the Rio docks and the after-work sambas, which included partido alto.

Partido alto in this sense (repentista) is samba wherein there is a chorus sung by everybody, and improvised verses sung by anybody who dares step forward. Aniceto was the master, reputed to be the best partideiro in Brazil.

This record includes songs by A-tier guest composers, including Dona Yvonne Lara, Roberto Ribeiro, Clementina de Jesus, João Nogueira and others…and includes venerables Argemiro Patrocínio and Casquinha (both of the Velha Guarda da Portela) on pandeiros.

Aparecida – Samba Afro Axé

Maria Aparecida Martins, whose artistic name was simply “Aparecida”, was born in the city of Caxambu, Minas Gerais (in 1939) and moved with her family to Rio de Janeiro at ten years of age.

She began composing at thirteen and was, after Dona Ivone Lara, the second woman to have a composition selected to represent a samba school in Rio’s Carnival (A Sonata das Matas, for Caprichosos de Pilares).

Aparecida’s music is deep roots samba, with lyrics for the most part based in candomblé. She passed away in 1985.

Argemiro Patrocínio (Sublime Samba from a Refrigerator Repairman)

Argemiro Patrocínio was a member of the Velha Guarda da Portela, and so, a consummate composer and singer (he was also a masterful pandeirista – tambourine player – and entered the school as a ritmista, rhythmist (or percussionist). Although he had songs recorded by acclaimed artists on major labels, his principal source of income was as a refrigerator repairman. He lived in the Rio neighborhood of Madureira.

His only record was produced by Marisa Monte (whose father was a director of Portela in the ’70s), when Argemiro was 80 years old. The arrangements are sparse and exquisitely tasteful, including the cello of Jaquinho Morelenbaum, the violin of Nicolas Krassik, the flute and clarinet of Dirceu Leitte, the harmonica of Rildo Hora, the accordion of Waldonys, and the voices of Zeca Pagodinho, Teresa Cristina, Moreno Veloso, and Marisa Monte.

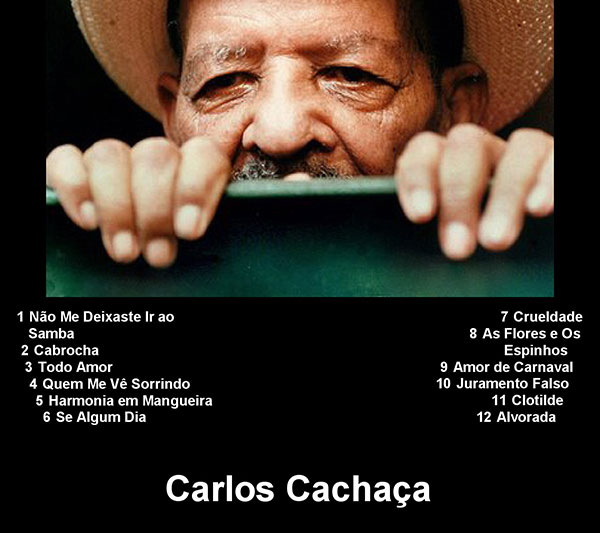

Carlos Cachaça of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

This is a great record! Recorded in 1976, when Carlos Cachaça was 74 years old. All compositions are his, some together with Cartola, and the famous “Alvorada” written together with Cartola and Hermínio Bello de Carvalho (Carlos wrote the “A” part).

It was produced by Pelão, who several years earlier had produced a record by Nelson Cavaquinho and who had bucked the standard record company commercial production standards (they didn’t even want Nelson — known for his idiosyncratic style — to play guitar!), calling in Rio’s great players and doing the production straight, as if the musicians were sitting in front of one playing and singing. What inspired Pelão’s intransigence? For one thing, this was his first job ever producing a record! He didn’t really know what he was doing, but whatever he did it was going to be his way!

After Nelson Cavaquinho, Pelão implored to be assigned as producer of Cartola’s first record, a wish which was granted. But Marcus Pereira, owner of the small label behind the recording, didn’t like the record and didn’t want to release it. Pelão complained to a friend of his, influential journalist Maurício Kubrusly, who the next day published an article (translating here): “Here Comes the Best Record of the Year — Cartola’s First LP!” The record was released and was a huge critical success, with solid sales. It’s still in print.

Unlike Carlos Cachaça’s only record. Which included Meira (teacher of Baden Powell and Raphael Rabello) on guitar, Canhoto on cavaquinho, and Marçal playing percussion, among other amazing musicians.

Carlos Cachaça was one of the founders of the Mangueira samba school. He was born in Mangueira, and despite his nickname (his real name was Carlos Moreira de Castro) he was not a drunk (cachaça being Brazil’s close cousin to rum). The story is that he was at a party with two other guys named “Carlos” and given that he didn’t drink beer — preferring to sip cane liquor — he got stuck with the name. Defenders are quick to point out that he worked his entire working life at Central do Brasil (the train terminal) in various capacities and never missed a day.

That was his employment. Samba was his calling.

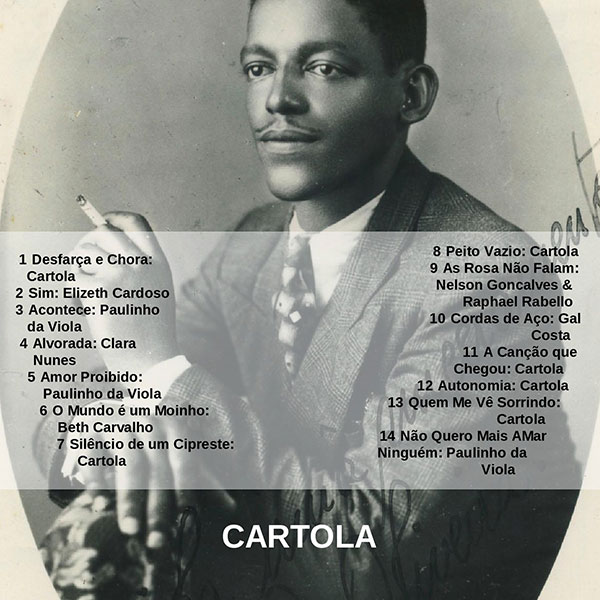

Cartola – Raízes (Magnificent Music from the Man from Mango Hill)

Cartola was a founder of the Mangueira Samba School (Mangueira is a favela in Rio; its samba school one of Rio’s most storied). It was he who chose Mangueira’s mythic colors — green and pink — the colors of the mangas rosas (pink mangoes) hanging amidst the green leaves of the mango trees which gave the neighborhood (albeit indirectly) its name. When the colors were criticised as an inelegant combination, rather than point out the obvious, he said that pink was for love and green was for hope, and how could love and hope not go together well?

As a boy Angenor de Oliveira worked construction, wearing a bowler derby — a cartola — to keep his hair from getting dirty. He composed Mangueira’s first samba enredo (marching samba), and he went on to write scores of most-highly-regarded songs (art songs, really), a number of which were recorded by Brazil’s best-known recording artists of the time (including Carmen Miranda). He was also tapped by Villa-Lobos for a recording by Leopold Stokowski, Native Brazilian Music. The composer never made any money to speak of, and in the 1940’s he dropped out of site, most people assuming he was dead.

In 1956 journalist Sérgio Porto (he often published under the pseudonym “Stanislaw Ponte Preta”) was having a cafezinho in a bar in Ipanema when a grizzled man with missing teeth walked up to the bar and ordered a cachaça. Sr. Preta gathered himself up and asked if by any chance he was standing face-to-face with the great composer Cartola — and the reply was in the affirmative. Cartola had been washing cars nearby and taken a break for fortification.

Cartola’s “rediscovery” led to another opening up of his compositions, and in addition to his own recordings of his work he has been recorded by Gilberto Gil, Gal Costa, Paulinho da Viola, Beth Carvalho, Clara Nunes, Clementina de Jesus, Elis Regina, Marisa Monte, and others. From 1963 to 1965 Cartola owned and operated a nightclub devoted to samba, Zicartola (the name combining his with that of his wife “Zica”, who ran the kitchen). Forgotten sambistas were brought back to the public and new ones introduced (Paulinho da Viola first performed there…his first earnings were the bus fare he couldn’t afford).

Cartola died in 1980.

Chico Buarque da Hollanda – Coletânia

Elton Medeiros, Candeia, Nelson Cavaquinho, Guilherme do Brito – Quatro Grandes do Samba

Elza Soares & Miltinho (gafieira)

Elza Soares’s first record was called A Bossa Negra de Elza Soares, “bossa negra” being used to emphasize the essential “blackness” of the music and to emphasize that the term “bossa” was being used in its original connotation of something swingingly hip and cool.

She sang samba in style called gafieira, big band samba meant for dancing by couples (gafieira is experiencing a resurgence in Rio these days, in clubs in the neighborhood of Lapa). And was married to a footballer considered by many to have been greater than Pelé: Garrincha.

Elza’s still at it, singing and scatting, the Undisputed Queen of real Bossa!

Paulinho da Viola – Meu Tempo é Hoje

Paulinho da Viola’s father César Faria – who played guitar with chorão (somebody who plays the Brazilian style of music called choro) Jacob do Bandolim – wanted for his son a more secure life than that of a professional musician. And so Paulinho studied economics, his first job finding him behind the window of a bank in Rio de Janeiro, working as a teller.

And one fine day producer Hermínio Bello de Carvalho recognized the son of the great César Faria as he stood before him at the bank. Hermínio asked Paulinho if Paulinho would like to be introduced to the composers of the of the Portela samba school. Of course!

They — in their trademark white hats trimmed in blue — asked the timid (he’s still timid) Paulinho if he’d written anything. Paulinho replied that he’d written the first verse of one song. They asked him to sing it, and he did.

Casquinha (now in his nineties), sitting in the back, asked Paulinho to repeat the verse…and on the spot Casquinha came up the second verse. Recado (Message) is now an important part of the Great Brazilian Songbook, as are many, many, many more of Paulinho’s (and friends’) compositions, and Paulinho da Viola has been a proud member of Portela for decades!

Musical Genre: Choro

A Música de Donga (Who the Hell is Donga???)

Donga is one of the most important people in Brazilian music, a guitar player born in Rio de Janeiro of a Bahian family. He was one of Pixinguinha’s Oito Batutas (Eight Batons, but in the slang of the day, Eight Cool Guys). He swang in Bahian samba, in choro, and in pontos de macumba (songs based in the Afro-Brazilian religion of Rio de Janeiro).

He was one the eminent people who hung out at the house/salon of Tia (Aunt) Ciata, the immigrant from Bahia in whose house choro was played in the front room, while candomblé ceremonies and and samba-de-roda took place out back (candomblé was outlawed at this time).

In 1916 a song which would come to be called Pelo Telefone was “composed” en masse by the crew at Tia Ciata’s, and it was copyrighted by Donga. It was the first carnival samba, the hit of Carnival, 1917.

The rest is history.

A Música Genial de Pixiguinha (vários regionais tocando/various groups playing Pixinguinha)

Turíbio Santos – Choros do Brasil

Musical Genre: Música Instrumental

Baden Powell – Coleção 50 Anos

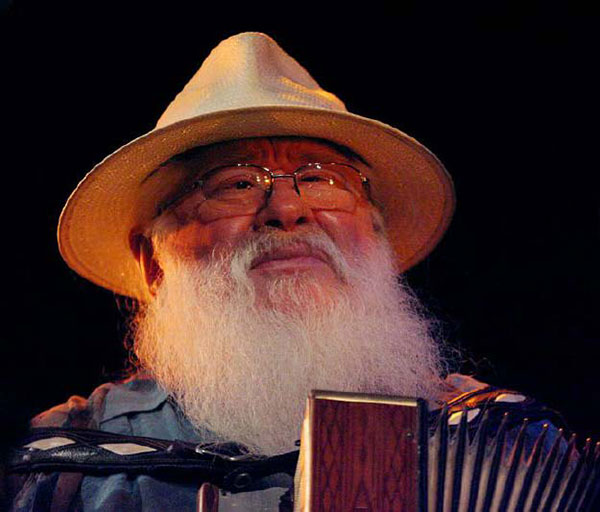

Hermeto Pascoal – Cérebro Magnético (The Sorcerer!)

This record has 13 tracks.

If Harry Potter’s school Hogwarts had a professor of music, it certainly would be Hermeto Pascoal. Hermeto was born in Lagoa da Canoa (Lagoon of the Canoe), Alagoas (the state immediately to the north of Bahia, which at one time was part of Bahia) and when he was several years old he was taken with his parents to live in Olho d’Águia (Eye of the Eagle), also in Alagoas.

An albino, Hermeto was forced to spend a lot of time indoors away from the fierce Brazilian sun, and he spent his time learning the concertina and pandeiro (tambourine).

He listened to everything, from the sounds of nature in his backlands villages to whatever records he could get his hands on, from classical to jazz, pulling these diverse resources into his iconoclastic compositions, bending and breaking what others considered to be strict rules of harmony and rhythm. He was taken up by Miles Davis and others, providing compositions for and recording on records in the United States.

Now in his eighties, Hermeto is as active and prolificly inventive as ever!

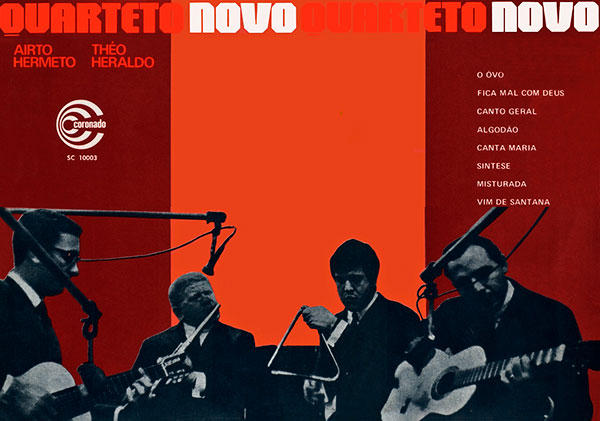

Quarteto Novo: 1967, com/with Hermeto Pascoal, Airto Moreira, Heraldo do Monte, Theo de Barros

Released in 1967, this stunning record is what American jazz might have sounded like had it been born and bred in the Nordeste (Northeast) of Brazil. Phenomenally heavy and soars and sings like a uirapuru.

There are 8 songs on this record.

Gilson Peranzetta, Sebastião Tapajós, Altamiro Carrilho, Maurício Einhorn – Encontro de Solistas

Chau do Pife – Memório dos Passos (forró com pífano/fife)

A “pife” or “pífano” is a fife, a simple flute with bored holes, almost certainly mankind’s first non-percussive musical instrument.

Chau is from the interior of Alagoas, and his father planted beans, manioc and corn. In order to keep marauding birds from eating the corn, Chau’s father gave Chau a pífano with four bores with which to whistle in the field…Chau became a wandering incipiantly-musical boy-scarecrow, so to speak. In order to make his task less onerous Chau would play — as well as he was able to and within the limitations of his “instrument” — melodies. Seeing this, Chau’s father presented Chau with a pífano with six holes, and the kid was on his way.

Now gracefully edging into older age, Chau sings like a symphony of birds! Accompanied by triangle and zabumba and accordion (making it forró, in other words). No wonder this record is called “Memório dos Pássaros” (Memory of the Birds)!

Sivuca & Quinteto Uirapuru

Musical Genre: Bossa Nova

Bossa Brasil (coletânia/collection: velhas/old bossas & novas/new bossas)

Celso Fonseca & Ronaldo Bastos – Paradiso

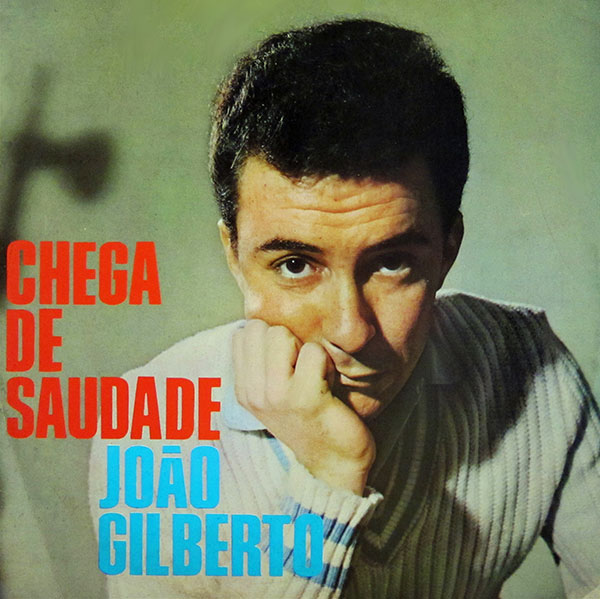

João Gilberto – Chega de Saudade (o primeiro LP de João/João’s first LP, 1959)

Bossa Nova has two roots: one in American West Coast cool jazz, the other in samba. João Gilberto, of Juazeiro, Bahia, brought the samba. He played on his guitar the rhythms he heard on the streets of his town on the São Francisco river, utilizing cool and complicated jazz chords. In Rio he fell in with America-infatuated would-be cool kids who thought that samba was very uncool, and showed them that they were very very wrong. He became their avatar.

In a blind listening test, when presented with João Gilberto, Miles Davis growled: “Give that five stars (the maximum)…that guy’d sound good reading the newspaper!”

To this day Sr. Gilberto refuses to say he sings bossa nova. If you ask him, he sings samba. And that’s cool.

Velha Bossa Nova – Coletânia de/Collection from 1964. Muito jazz/Very jazzy!

Musical Genre: Sambalanço

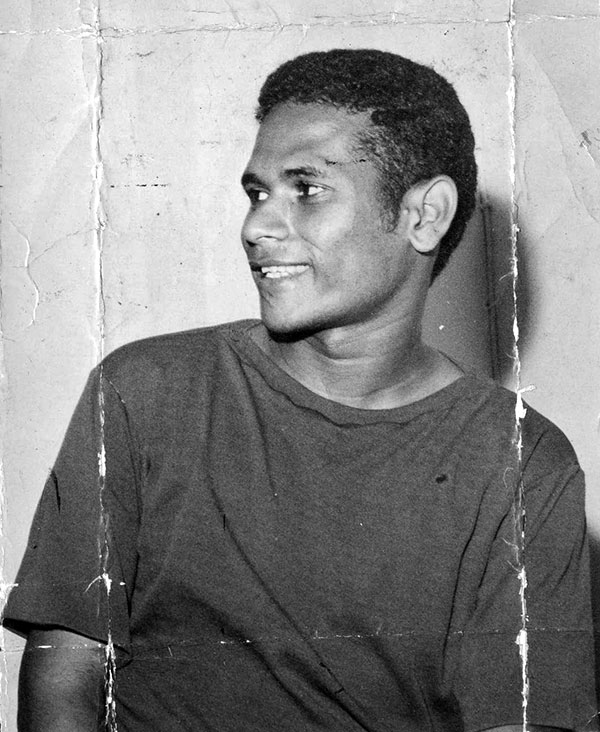

Jorge Ben – Samba Esquema Nova

Half-African Jorge Ben (Jorge Benjor) is Brazilian finger snappin’ caaaaatchy grooooooovy! He joined the army as a teenager which meant he spent too much time hanging around the barracks with nothing to do. So his mother bought him a guitar and a how-to-play book, and he went sideways from the bossa nova which ruled at the time, inventing his own thing based in samba and other Brazilian rhythms.