Bahia is a hot cauldron of rhythms and musical styles, but one particular style here is so utterly essential, so utterly fundamental not only to Bahian music specifically but to Brazilian music in general — occupying a place here analogous to that of the blues in the United States — that it deserves singling out. It is derived from (or some say brother to) the cabila rhythm of candomblé angola… …and it is called…

Samba Chula / Samba de Roda

Sacando a Cana (Bagging the Sugar Cane) written and sung by Raymundo Sodré of Ipirá, Bahia.

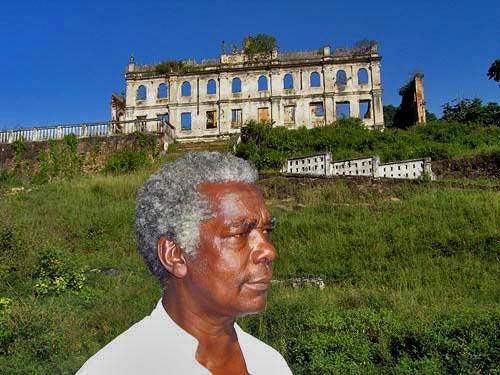

Mother of Samba… daughter of the semba carried to Bahia by Bantus ensconced within the holds of negreiros entering the great Bahia de Todos os Santos (the term referring both to a dance and to the style of music which evolved to accompany that dance; the official orthography of “Bahia” — in the sense of “bay” — has since been changed to “Baía”)… evolved on the sugarcane plantations of the Recôncavo (that fertile area around the bay, the concave shape of which gave rise to the region’s name) — in the vicinity of towns like Cachoeira and Santo Amaro, Santiago do Iguape and Acupe. This proto-samba has unfortunately fallen into the wayside of hard to find and hear…

There’s a lot of spectacle in Bahia…

Carnival with its trio elétricos — sound-trucks with musicians on top — looking like interstellar semi-trailers back from the future…shows of MPB (música popular brasileira) in Salvador’s Teatro Castro Alves (biggest stage in South America!) with full production value, the audience seated (as always in modern theaters) like Easter Island statues… Carlinhos Brown’s Museu do Ritmo (Rhythm Museum; an entertainment venue) all done up Bahian faux tribal showbiz style…glamour and glitz and press agents…

And then there’s where it all came from…the far side of the bay, a land of subsistence farmers and fishermen, many of the older people unable to read or write…their sambas the precursor to all this, without which none of the above would exist, their melodies — when not created by themselves — the inventions of people like them but now forgotten (as most of these people will be within a couple of generations or so of their passing), their rhythms a constant state of inconstancy and flux, played in a manner unlike (most) any group of musicians north of the Tropic of Cancer…making the metronome-like sledgehammering of the Hit Parade of the past several decades almost wincefully painful to listen to after one’s ears have become accustomed to evershifting rhythms played like the aurora borealis looks…

So there’s the spectacle, and there’s the spectacular, and more often than not the latter is found far afield from the former, among the poor folk in the villages and the backlands, the humble and the honest, people who can say more (like an old delta bluesman playing a beat-up guitar on a sagging back porch) with a pandeiro (Brazilian tambourine) and a chula (a shouted/sung “folksong”) than most with whatever technology and support money can buy. The heart of this matter, is out there. If you ask me anyway.

![]()

There are also the Bahian musicians who came of age in the ’60s, famous and wealthy and talented, but who, being popular stars (and at times downright pop stars) only intermittently sing Bahian music…who are more musicians-from-Bahia than Bahian musicians (although Maria Bethânia has really jumped into Bahian samba over the last years, the music of her hometown Santo Amaro, doing it beautifully! Her voice, like fine aged oak saturated with the characteristics of a rich and complicated red wine, is more expressive now — in her late 60s — than it ever was in previous decades).

Their (particularly Caetano and Gil) defining musical movement was Tropicália, which in some respects had more to do with San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury than with Bahia (and with bell-bottoms than with the fedoras worn then and now by the chuleiros)…

![]()

And then, pilgrims, there was Dorival Caymmi, who emigrated from Salvador to Rio in the ’30s, looking for work as an illustrator. He took his guitar with him and Brazilian music, always blessed, has never been the same.

Caymmi had a close friend by the name of “Zezinho”, and Zezinho had — in addition to his wife and family proper — a lover and four children living in another area of the city. Dorival asked his friend one day what excuse he gave when going to visit his second family…

Zezinho would send a telegram to himself, his friend replied, informing him of business requiring his attention in Maracangalha. Upon returning home to his “official” family Zezinho never failed to take along with him a large sack of sugar as evidence of where he’d been. Dorival, intrigued with the poetry in the name of the community used in this subterfuge, composed “Maracangalha” in one sitting (below sung by Salvador resident Jussara Silveira, with guitar playing and arrangement by Luiz Brasil, also of Salvador, of course)…

Both Caymmi and Assis Valente (from Santo Amaro, Bahia, although like Caymmi he migrated to Rio looking for work) wrote for Carmen Miranda, whose pre-USA career of comic exaggeration was as a small-but-charmingly-voiced and stupendously popular samba singer.

Bahia’s Greatest Griot

Bule-Bule (Antônio Ribeiro da Conceição), hailing from the tiny community of Antônio Cardoso — where the Recôncavo gives way to the sertão — was brought up in the repentista tradition wherein improvised rhymed verses having to do with everything from events of the day to fables of northeastern Brazil to jocular putdowns of competing repentistas are sung to the accompaniment of the viola caipira. Bule-Bule also writes, expressing himself in a traditional literary form of the Northeast, the cordel. And nonpareil he is a sambador rural, utilizing a style of samba — styles really — not often heard outside of their territory stretching from the sugarcane producing region near the coast into the dry hinterlands of the Bahian interior…his music sonically entwining the history, tradition, and beauty of a select area of the planet.

This is a short clip of Bule-Bule dancing in the style native to his region (as with the first clip at the top of the page, I got it with an Olympus C-5060, all I had at the time, but the spirit’s there…).

Hot Buttered Soul, Straight Outta Cachoeira!

Os Tincoãs, with their hauntingly beautiful vocals, were named for a suitably beautiful bird common to their area (the tincoã) reputed to have the power to warn humans of impending danger…the group comprising three vocalists hailing from Cachoeira, Bahia. 1960 was their first year of existence, but they really found their footing three years later when Erivaldo left the ensemble and Mateus Aleliua — bringing with him an ethos founded principally in Bahia’s houses of candomblé — joined Heraldo and Dadinho.

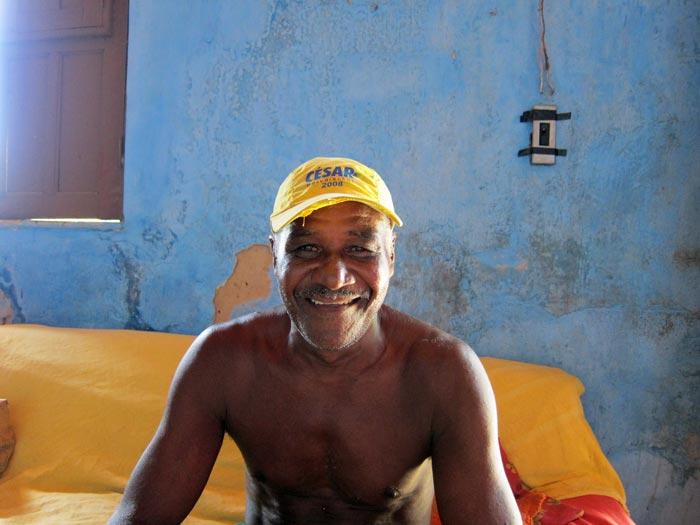

Heraldo and Dadinho have since passed away, but Mateus (to the right, above) is still active, having co-written another candomblé-based song which was the hit of Carnival a few years ago (Maimbê Dandá). Unfortunately none of Os Tincoãs’ records are available anymore.

Cordeiro de Nanã (Nanã’s Lamb): the chorus is taken straight out of Bahia’s houses of candomblé. The ethos of the group — as described by Mateus — combined the music of candomblé with black American spirituals.

The Musician Who Roared Back from the Dead

In the manner that Machito and Mario Bauzá took the music of Cuba far beyond its “simple” origins, Raimundo Sodré has taken the music of his cradle (samba-de-roda, which brightens and leavens festas across the Bahian Recôncavo with its characteristic syncopated hand-clapping and hip-rattling dancing…) and woven it into something at once sophisticated, moving, African, Brazilian, and constantly evolving. Sodré was one of those overnight media sensations whose trajectory into the klieg lights was years in the making… While laying in a hammock outside his simple house in the village of Bom Jesus dos Pobres, on the far side of the bay from Salvador, with a Bach melody dancing its way through through his mind’s ear, Sodré thought to adapt a tune of his to this style, and then bend it and let it spring back into a chula. He combined it with what had begun as nonsense lyrics he’d happily clapped his hands to and sung repeatedly while in an inexpensive hotel in Salvador…”A massa da mandioca mãe”…let it assemble itself, and then after passing the drift along to a friend, got great lyrics back. It was a protest against the dictatorship of the time. His wife sent a tape to PolyGram, Sodré was called in, recorded, had a huge hit, and appeared in Brazil’s nationally-televised 1980 song contest.

He came in third place, but was the popular favorite (so much so that the first-place winner was booed by the audience), and the career of this backlands boy took off like a rocket out of the brush. In A Massa, Sodré sings the lines: “No cabo da minha enxada, não conheço coroné.” “At the handle of my hoe, I don’t know the coronel (the South American big man).” This was defiance, of the men who dominated the land and the people on it. In 1981 Sodré sang in the presence of one of these men, standing his ground and openly criticising the man to his face, in front of the audience. That was the end of Sodré’s career, and of his peaceful presence in Brazil.

Threatened with losing more than just his career, he fled to France and spent 19 years there, returning to Bahia in 2000. He recorded the independent production Dengo (I was one of the producers), released in 2007, and is vigorously doing what he does…play, sing and dance.

Sodré is from the town of Ipirá in the Bahian interior. His mother was a filha-de-santo (one of the women who in candomblé ceremonies receive, are possessed by, the orixás, or in this case rather, nkisis, because this was a house of candomblé angola. His aunt was mãe-de-santo, head priestess. Before learning to play guitar, at the hands of his mother (who taught him the chulas of the region), Sodré learned to drum.

His father had begotten him but never married his mother, and Sodré spent summers with his father in his hometown, Santo Amaro. Sodré eventually moved with his mother to Salvador, to the neighborhood of São Caetano. Today he lives in Salvador’s neighborhood of Boca do Rio. Below find a clip a filmed (with a simple camera) some eleven or so years ago, in the house of Roberto Mendes. Sodré and I were rolling around Santo Amaro on a Saturday afternoon and stopped in at Roberto’s house, where he was hanging with Agnaldo (rebolo) and Ecinho (cavaquinho). Out came the instruments and the result — a series of traditional songs and Roberto Mendes compositions — follows:

Romance is HUGE in Bahia!!! Arrocha!

In Zurich some years ago I met a Bahian guy named…Pablo. He pulled up in front of the building where I was staying with members of a Brazilian music show I’d written (directed by dear Toby Gough), and jumped out of a ’60s era Ford Mustang. He had hair that swooped up rather oddly in front, and a big nice-guy smile, and was introduced to me by Jau, a Salvador singer of some renown.

Pablo was around a lot during our three-week stint in that marvelous city, and I just figured he was hanging out, probably having arranged a monied Swiss lover back in Salvador. During high Carnival a number of years earlier I was with friends banging around, and we met a couple of cute girls in the Praça Municipal, where the elevator connecting lower and upper cities gives on to. Out of a loudspeaker somewhere came a bolero with an updated sound, sung by an earnest, high-range voice full of hurt and longing. The girls jumped up from the table, proudly announcing that this was “arrocha”, a style of music from where they were from up bay a bit. They came together and danced a dance so sensuous that the lambada looks a staid and stiff waltz by comparison…

Well, a couple of things happened. One of the girls married one of my friends, and this music became the de rigueur sound of Bahia’s small towns and Salvador’s poorer neighborhoods. Then, what? a couple of years ago I’m almost home, and I run into some musicians I know…there’s a recording studio a couple of houses down from my building. They say “Pablo’s recording, come on in!” So in I go and who do I meet other than the nice guy with the swooping hair. My friends tell me “Pablo sings arrocha…” He tells me he owns a kebab place in Ribeira, gives me his card, and says come on by. I love kebabs but haven’t managed to get out there yet…

And then several years ago I’m at home, at night, and an arrocha drifts in from out there somewhere in rough, ready, and suddenly very romantic Salvador…a high voice full of yearning and suffering and ecstatic desire, the music carried along and supported by the underlying churning of the bolero. My kid tells me “That’s Pablo.”

It turns out that it was Pablo who took the bolero, old man’s music, and made it the ubiquitous sound of young Salvador and Bahia. I’ve complained about arrocha plenty. The musicality falls firmly into the category “hugely popular to the non-discerning public”; but the dance, the movement of thigh and buttocks, is seriously celestial in the sensual sense.

And you know, Pablo’s musical sensibility might not be Hermeto Pascoal’s, but I like him, and a lot of Bahianos will happily dance, spoon and swoon to him. And that’s not always such a bad idea.

Below Pablo sings about the genie in the beer can; his only wish is that she will return to him!