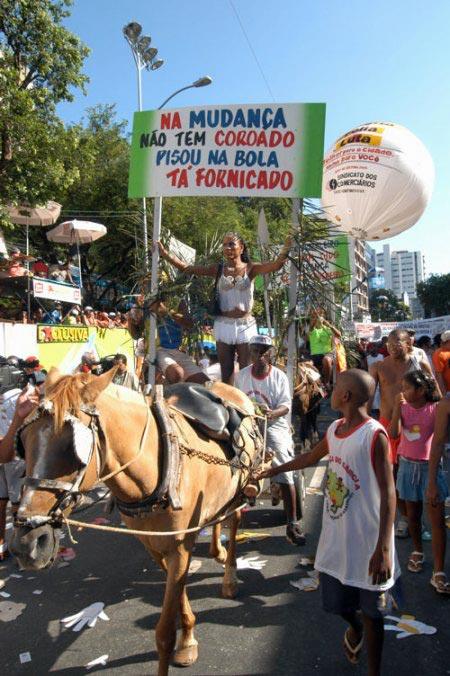

Pre-Carnival: The fuzuê (foo-zoo-EY; fuzuê is slang for something like “problematic confusion”) takes place as a parade along the waterfront in Barra on the Saturday before official Carnival begins. It consists of real-deal, true-blue, people-of-the-land cultural manifestations, produced by people humble and poor and often wickedly oblique:

Straightforward, unadorned utility makes things easy to understand. A car takes you places. A telephone is for communicating (okay, maybe that’s not such a great example anymore). Cultural manifestations usually have a psychological utility. And where the human mind is involved it’s common for things to be anything but straightforward.

Take the Mandús for example (mahn-DOO). They dance through the streets of Cachoeira during festas. Like little men with big fabric “heads” in the form of squat cylinders (the fabric being one that the local women use to make skirts; the fabric draped over, at the topside of the “head”, a round, woven sieve). Waist-high arms extend straight-out, terminating in big flat hands.

The Mandús jiggle and play on their way down the street, sometimes slapping fellow party-goers on the butt with those big hands. WTF?

Those are local boys inside. The brincadeira (game) was inspired in the cult of the Egunguns on the island of Itaparica down the river and across the bay. The Egunguns are ancestral spirits who return to manifest themselves dancing under highly brocaded fabrics supported at top by a square…something.

The Mandú are dancing, partying, butt-slapping pretend ancestral souls. What, if anything, are they beyond that?…

Then there are the cabeçorras (ka-beh-SAW-hahs). Tall “men” topped by big paper-maché heads, with big waists (formed by something like a wide hula hoop under the fabric covering their bodies) rolling this way and that like a whole lotta butt-shaking is going on, these men (the ones being represented) being the top, the biggies, society’s captains.

The cabeçorras got started in the misty past when real bigwigs would parade their exalted selves down the streets at popular festivals, nodding and waving solemnly to the hoi-polloi.

In mockery some of the hoi-polloi got themselves duded up to likewise parade per the have-it-alls of their time, making to order the heads of specific powerful personages, waggling and butt-shifting their way ridiculously down the street, nodding and waving to the common people over whom they “lorded”.

“Zambiapungo” is one of the Bantu names (“Bantu” encompasses a wide range of peoples) for the Supreme God, the great, indescribable, above-and-beyond-all divinity. In the Bahian communities of Nilo Peçanha, Cairu, Boipeba (the area of dendenzeiros, the palm trees from which palm oil is extracted from the seeds of the red fruit growing profusely beneath the trees’ foliage) the zambiapungas, dressed in brightly colored, body-covering costumes with their faces covered as well, holes for eyes and mouth, a huge sewn-on nose…march on the morning of the day preceding the Day of All Souls, making racket fit to raise the bodies of all those from whom their souls have been separated in order to drive away (originally anyway) the bad souls in the vicinity. This would seem to be the adaptation of an African custom to fit the Christian calendar.

Some things can be explained. Other things must be alluded to. Those which surmount the rational must be experienced. Thus is Carnival in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil…

![]()

Carnival in Salvador is it, baby! That is, of course, if parties and crowds are your thing. Nowhere else comes close. Carnival Bahia is not nubile women in feathers high up on floaters à la Carnival Rio. It’s YOU out there on the streets doing it ’til you drop. Carnaval (as it’s spelled in Portuguese) 2023 begins () and it runs through () — officially. Unofficially (and actually) it runs to the morning of Ash Wednesday, (), and then continues in the arrastão (roundup), which starts Wednesday morning at the Farol da Barra and winds its way along Avenida Oceanica to Ondina.

And then there you are there at Ondina’s lovely beach, where the party continues…

Carnival in Salvador, put simply, is a parade — or two parades actually (on the first and second circuits above) — of trio elétricos. A trio elétrico is a done-up semitrailer, loaded with thousands of watts of sound equipment and with a band playing on top. They parade very slowly along one of two Carnival circuits, one closer to the city center, running from Campo Grande (literally Big Field, Salvador’s central park) to Praça Castro Alves (named for Antônio Frederico de Castro Alves, the Bahian poet who, among other things, wielded his mighty pen against the injustices of slavery and political oppression), and the other running from Barra to Ondina, along the Atlantic Ocean.

The first trio to exist was an old car (’29 Ford) with a driver (Muriçoca, a nickname meaning “mosquito”), and two musicians (Dodô and Osmar) in the back (the car can be seen in the museum at the Lagoa da Abaeté in Itapoan; it debuted in 1950).

The following year Dodô and Osmar, who played electrified string instruments of their own devising and called themselves a dupla elétrica, added friends, Reginaldo Silva and Themístocles Aragão (who took turns playing, only one at a time) on the triolim (tenor guitar), thus becoming a trio elétrico (having abandoned the jalopy for a Chrysler Fargo pickup truck).

That first time the fobica (jalopy) hit the avenidas (avenues) there came a point where Osmar yelled to the driver Muriçoca (Mosquito) to stop for a bit…but the car kept moving…Osmar yelling several more times…Muriçoca finally realizing what Osmar was saying and turning around to explain that the clutch and brakes had long gone out and he’d switched off the motor…the crowd was pushing them forward!

This first trio (okay, duplo) introduced frevo — an energetic style of music native to the Brazilian state of Pernambuco to the north (frevo comes from ferver, “to boil”) — into Salvador’s Carnival for the first time. Osmar’s son illustrious Armandinho Macedo is the local Jimi Hendrix of this style (among others), wailing away on his guitarra baiana (Bahian guitar, an updated version of the instrument invented by his father back in the ’40s). The trios form the nucleus of the major blocos. One pays to join a bloco and is given an abadá (a getup consisting of a done-up t-shirt — in this sense — although an abadá in reality is a long, flowing, sleeveless robe of West African origin), allowing one to parade with the bloco inside the cordão (rope carried by security personnel). The trios are to a great extent the face and fame of Carnival in Salvador, but as always, reality is more complex than the way it is usually presented…

Carnival blocos (blocks, as in groups of people) have marched for a long time in Salvador, and Salvador at one time had Carnival schools as well (there are several different names for Carnival agglomerations: blocos, schools, cordões (ropes), afoxés and ranchos…sometimes the names are used loosely, overlapping, definitions varying from person to person… another time…). They were usually groups of friends, or people who worked together or lived in the same neighborhood. After the idea of the trio elétrico caught on, with its musical firepower, another idea caught on…money! It turned out that a lot of people were willing to pay a lot of it, usually making monthly payments throughout the year, to accompany their favorite artists on top of a moving soundstage.

And as tends to happen when money rules music, the lowest common denominator wins out. Ironically a part of this process was the success in 1986 of a dumb song written and performed by two excellent musicians, Luiz Caldas and Paulinho Camafeu, Nega de Cabelo Duro (Fricote). Axé music was on! The trios with their frevo had already made Salvador’s samba schools obsolete in the mid-1970s and now, in terms of popularity, the Carnival revolution was complete. Axé music continues to dominate Carnival, together with samba-de-roda’s greatly coarsified bastard offshoot, Bahian pagode, axé (ah-SHEH) music being a commercial pop grab bag hybrid of whatever, including American/European danceclub styles (named for the West African life force axé, combined with the English-language music, in a derogatory dig at its pretensions, the name catching on nevertheless).

Television coverage of Carnival in Salvador is likewise dominated by the big commercial blocos, DVDs available after any Carnival in question undoubtedly (up to now, anyway) featuring the money bands. And in at least one respect a general good does come out of this: The commercial blocos provide work for any number of top-flight musicians who find such work in too-short supply during much of the rest of the year.

But there is more to Carnival than this! Thank god for the afoxés, and the blocos afros! Thank god the samba — with its Bantu-based swing — has come roaring back! The candle was reignited in 1975 with the creation of Bloco Alvorada (alvorada is the breaking of dawn) by a group of students (who have since of course matured into éminences grises, but without letting the samba die), and then oxygenated and brightened further in 1983 when Nelson Rufino organized Bloco Alerta Geral (“General Alert”, as in “All Points Bulletin”). Nelson went on to found yet another Carnival samba bloco in 2004, Amor e Paixão (Love and Passion)…three thousand Panama-hatted members marching and dancing in African-born homage to Dionysian ideals.

→ The three Carnival Circuits are: • The Campo Grande – Praça Castro Alves Circuit, also called the “Osmar” Circuit, or simply the “Avenidas”. • The Barra – Ondina Circuit, also called the “Dodô” Circuit. • The Pelourinho Circuit, also called the “Batatinha” Circuit.

The Osmar, or Campo Grande – Praça Castro Alves Circuit, is the original Salvador Carnival Circuit (going as far back as the 50’s anyway; the where and what of Carnival is actually something of a complicated story depending on when). Carnival’s official opening is at Campo Grande, and this is where the political bigshots sit and where the Carnival blocos are judged. The trios move away from Campo Grande and down Avenida Sete de Setembro (usually called “Avenida Sete” by the locals) to Praça Castro Alves. From there they swing around the corner and make their way back to Campo Grande by Rua Carlos Gomes, which runs parallel to Avenida Sete. The course takes six hours or so to run (“crawl” might be a better word!).

The denomination “Osmar” is in homage to one of the two creators of the trio elétrico. The Dodô, or Barra – Ondina Circuit, was added in ’92 (when it was very much secondary to the Campo Grande – Castro Alves circuit). The trios start at the Farol ( Lighthouse ) da Barra and wend their way up along the ocean to Ondina. The course takes some four hours or so. Nowadays there is a tendency for the bigger names to play this circuit, as it is seen as more desirable (a view I don’t necessarily share) by a lot of Salvador’s middle-class youth, the ones with the money to join the bigger blocos. The denomination “Dodô” is in homage to the other creator of the trio elétrico.

The Batatinha Circuit runs through Pelourinho, the Old City. The denomination “Batatinha” is in homage to Batatinha (Oscar da Penha), a resident of Pelourinho during his lifetime, sambista and composer of wonderful music. Batatinha died in 1997 at 72 years of age, and if you’re close to Campo Grande you can stop in at Bar Toalha de Saudade — owned and run by Batatinha’s son Vavá — on the Ladeira dos Aflitos (not too far from the top of the street, on the right-hand side as one descends). As a matter of fact, the bar was named for a song of Batatinha’s wherein he recounts the true story of a chance meeting during a Carnival years ago…a lovely young woman emerging from nowhere, asking Batatinha if she might borrow the towel he was carrying (which was a part of his samba-school kit) to dry her face. She thanked him for his kindness and melded back into the crowds, leaving Batatinha filled with nothing but longing, her sweet fragrance, and thoughts of what might have been…

During Carnival Pelourinho’s praças (public squares) are replete with music in a multitude of Brazilian styles…it’s especially gratifying to hear the big horn band of Fred Dantas playing the carnival sambas and marchinhas from Brazil’s golden age of music (which corresponded with the age of the Great American Songbook). It’s like stepping into a past even more vibrantly alive than the present.

The Mudança do Garcia (mudança is “change”) is a Carnival march from the neighborhood of Fazenda Garcia to Carnival at Campo Grande. It began as a protest by vereador (city councilman) Herbert de Castro against the lack at that time (the fifties) of paved streets, public illumination, and constant fresh water in the area, the marchers carrying potties in protest, along with placards satirizing the politicians and their perfidious policies. The prefeito (mayor) of the time, Hélio Machado, because of the protest, actually saw to it that improvements were made in the area, but the cat was out of the bag and the mudança continues to this day, every Carnival Monday.