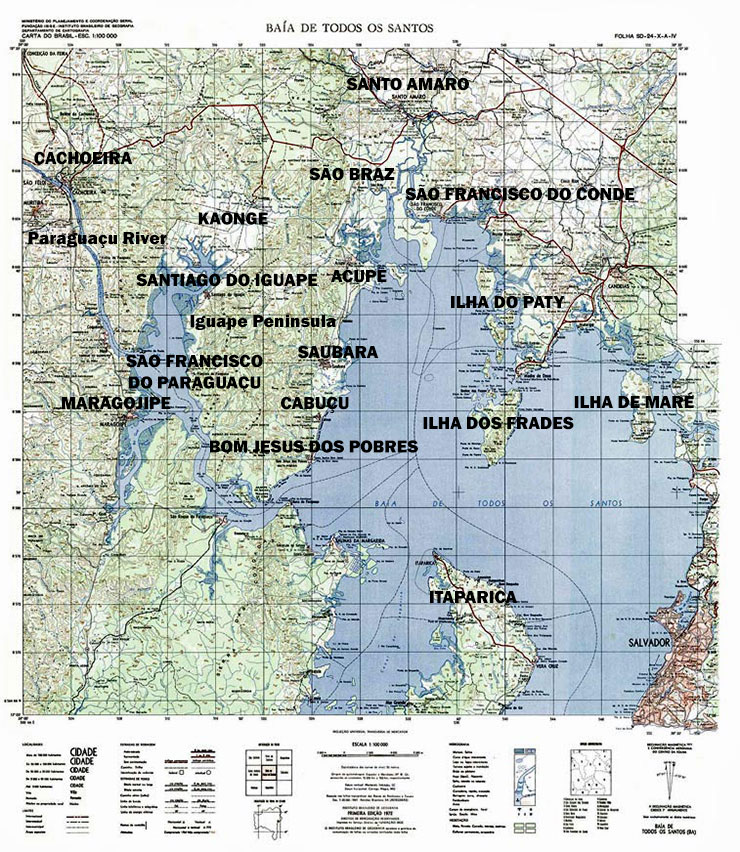

In Portugal a recôncavo (pronounced in Bahia heh-KAWN-kah-vo) is a concave-shaped area of land around water. In Brazil, with a capital “R”, the term refers specifically to the great Recôncavo of Bahia. The importance of this area to Brazilian history and society cannot be overstated. The importance of this area in the history of mankind cannot be overstated.

For more enslaved human beings entered this bay as final port-of-call than any other such during the entire period of human history. These people were stripped of everything and arrived with only their humanity and even that was to a great extent denied them. And yet it was their culture which — in non-material aspects (and aren’t those the most important and long-lasting?) — conquered the largest continental nation in the New World.

What does one find in the Recôncavo now? Small towns, little villages… some of the sugarcane fields are still there, the cane hacked out by poorly paid workers rather than the enslaved. Many of the villages were founded as quilombos, a term which in Angola means “village” (kilombo) but which in Brazil carries the inseparable connotation of having been founded by enslaved who’d run for a tenuous freedom.

This is a work-in-progress. And rather than move straight through (given that I’m working things out here) I’m going to bring things into focus across a wider (from top to bottom!) spectrum, like interlaced photos on the internet…

The Paraguaçu (para-gooah-soo) has its origins in Bahia’s Chapada Diamantina, the chain of extremely old and well-worn mountains which runs through the state on a north/south axis.

The Simmering, Muted Majesty of Cachoeira, Bahia

Cachoeira means “waterfall”, and the river above Cachoeira was, when Cachoeira was founded, falls and rapids, Cachoeira having been deliberately situated at the farthest navigable point into the Bahian interior on a river debouching into the Baiá de Todos os Santos (this making Cachoeira a deliberately logical entrepot between Salvador and the sertão…backlands).

The cachoeiras have been replaced since by an enormous hydroelectric dam (Pedro do Cavalo, built in 1985), behind which lies a vast reservoir (Pedra do Cavalo also), source of the Salvador metropolitan region’s water.

And transportation from the interior to Salvador is no longer through Cachoeira and then down-river by boat; it’s through the sprawling market town of Feira de Santana and then down the crowded federal toll road BR 324. For this the once dynamic town of Cachoeira has slipped into languorous torpor over the still and nacreous Paraguaçu.

Cachoeira’s founding — like Rome’s — is attributed to a legendary figure, in Cachoeira’s case this being Caramuru, a Portuguese who received this name from the indigenous natives who devoured the seven less fortunate companions who together with pre-Caramuru Diego Álvares Correia had survived a shipwreck off the coast of what would become Salvador.

Caramuru (so called by the natives, the story goes, because in their language that signified a moray eel and he came out of the water skinny and wet) did better than simply survive. He would marry (among others) the daughter of the king and father several Bahian dynasties.

But irrespective of Cachoeira’s founding’s truth it was not until the potential in the area’s massapê (a rich alluvial soil) for sugarcane production was realized that the town’s foundation was begun in earnest. It was then that two of these nascent dynasties — formed by the marriages of Paulo Adorno with Caramuru’s daughter Felipa Álvares, and Afonso Rodrigues with Felipa’s sister Magdalena Álvares — were established upon the region’s first sugarcane plantations and sugar mills, and in the town.

Paulo Adorno’s great-grandson Álvaro Celestino Adorno built Cachoeira’s first Catholic church, Nossa Senhora do Rosário (Our Lady of the Rosary) on a hill overlooking the river between 1595 and 1606, the name being changed in 1637 to what it is today: A Capela de Nossa Senhora da Ajuda (the Chapel of Our Lady of Help). The church was a necessary but not sufficient place of expiation for the engenho, the sugar mill, and the various of the big houses in the immediate area which at one time belonged to the mill, and which still stand. Álvaro’s great-grandson João Rodrigues Adorno rebuilt the church in roughly its present form between 1673 and 1687.

In the two photos above of the Capela d’Ajuda a small annex may be seen. This is a photograph-filled meeting room adjunct to a manor house the back of which faces the chapel across a small square on the hill there. The meeting room, the photographs in it, the manor house…all are tangible evidence of one more irony in a land so plentiful in such: Of all the lay Catholic religious brotherhoods and sisterhoods in Brazil (the world?), none have emerged at our end of centuries with the vibrant visibility of this one — A Irmandade da Boa Morte (The Sisterhood of the Good Death) — the members of which were and are at the rock bottom of a cruelly constructed economic ladder; they are African-Brazilian women past child-bearing age. In addition to being Catholics (and the following is one reason for the vibrance) they are people of candomblé. As one finds Catholic churches everywhere here (some in the most seemingly unlikely places), the Recôncavo is beyond rife with candomblé and the deities of Africa.

Arriving in Cachoeira — when coming from Salvador — is usually via state highway BA-420. But there’s an alternate route by which entry was (and is no longer) possible, which involved turning off of the main road and passing by the Lagoa Encantada (Enchanted Lagoon). Continuing along the dirt road one would pass on the left-had side the Roça do Ventura, the land surrounding house of candomblé jeje Zogbodo Malè Bogun Seja Hunde, wherein the deities revered aren’t orixás, as is common in Salvador, but voduns.

Below is a trailer for a never-made documentary about Ventura. It includes Mateus Aleluia of the legendary Tincoãs, a vocal trio from Cachoeira. Mateus was raised (religiously speaking) in the terreiro and much of the terreiro is in his music.

Ilê Axé Alaketu Oxum: Alto do Rosarinho

Yemanjá – Ogunté: Baixa da Olaria

Centro de Caboclo Jeremias: Ladeira Manoel Vitório

Candomblé de Dona Nilta: Alto da Levada

Ogum Meji: Ladeira Manoel Vitório

Ilê Axé Alaketu Oxum Apara: Ponta da Calçada

Candomblé da Dalva: Rua Senhor dos Passos

Candomblé de Dona Dionisia: Rua da Faceira no Caquende

Candomblé de Justo: Ladeira da Cadeia

Candomble de Dona Anália: Ladiera do Rosarinho

Casa do Samba de Dona Dalva. Rua Ana Néry, 19. Cachoeira-Bahia

São Felix

The Dannemann cigar business in São Felix was established by young Gerhard Dannemann (who would become “Geraldo” here in Brazil) from the German town which features in that such-a-wonderful story collected and retold by the Brothers Grimm: The Musicians of Bremen.

In the original version of this story, dating back some thousand years, the robbers were a bear, a lion, and a wolf…all heraldic images representative of the aristocracy. Bremen celebrated the three courageous musicians for their liberation of the town from these noxious and unnecessary parasites, their defeat to be paralleled by the liberation of the majority of Bahia’s inhabitants from (and to an imperfect degree) the slave-owning class on May 13th, 1888.

The Peninsula of Iguape

São Braz

Below find samba chula by João do Boi’s group (that’s João to the left in the black hat) with the first several minutes sung by Raymundo Sodré (yellow shirt, leather hat), viola (brasileira) played by Cássio Nobre (white sleeveless T), marcação (red drum) played by Zé Carlos there, and background vocals including Dora (Bahiana to the right)…

Saubara

Marujadas or Cheganças are a Brazilian version of the Portuguese Fandango. They are in a sense an Afro-Brazilian version of a Lusitanian version of epic Greek poetry…reciting — or singing rather, in groups of men or women — stories of battles and shipwrecks and heroic feats, particularly (in the Recôncavo) in defense of Bahia while fighting the Portuguese — while playing guiding rhythms out on pandeiros (Brazilian tambourines).

There’s a site devoted to the local marujadas: http://marujadadesaubara.org.br

Cabuçu

Electricity came to Cabuçu in 1972. Water through pipes in 1977.

Bom Jesus dos Pobres

In the 17th century the owner of the lands around where the village of Bom Jesus dos Pobres is now located — Padre Francisco de Araújo, great grandson of Caramuru — built a chapel here (beginning around 1640) devoted to the Senhor Bom Jesus. Within this chapel he was buried in 1659.

BA-878 from Santo Amaro to Saubara was constructed in 1966. In the following year it was extended to Bom Jesus.

Non-local people at sambas in this part of the Recôncavo (and occasionally in Salvador) wonder about the lady dancing samba de roda with the boat on her head… That lady is popularly known as “Rita da Barquinha” (Rita of the Little Boat). As a little girl in Bom Jesus dos Pobres she would see Dona Melica who then maintained the tradition…passing on the night of December 31st with the boat from house to house, accompanied by singing, dancing villagers, residents by turn placing into the boat offerings for Yemanjá.

The boat was then placed with the presents into the water at midnight — turn of the year — in hopes that the deity would look kindly upon the lives and safety of the fishermen who were the sustenance of the community.

The responsibility is now Dona Rita’s.

Santiago do Iguape

São Francisco do Paraguaçu

São Francisco do Conde

Kaonge

Islands in the Bay

Paramana, Ilha dos Frades